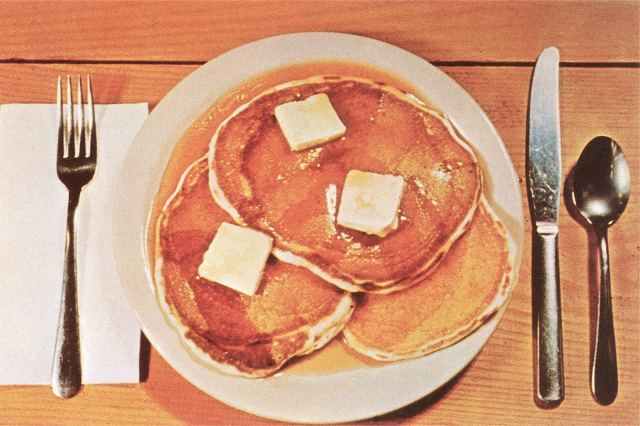

5 Discontinued Snacks We Wish Would Come Back

As far as ephemera is concerned, few things are as temporary as snack foods from the past. Snacking itself is an evanescent experience, a fleeting moment of between-meal indulgence or an inattentive nosh during a spectator event. But snacks are also a major part of American culture; snacking has doubled since the late 1970s, and according to the 2024 USDA survey “What We Eat in America,” 95% of American adults have at least one snack on any given day.

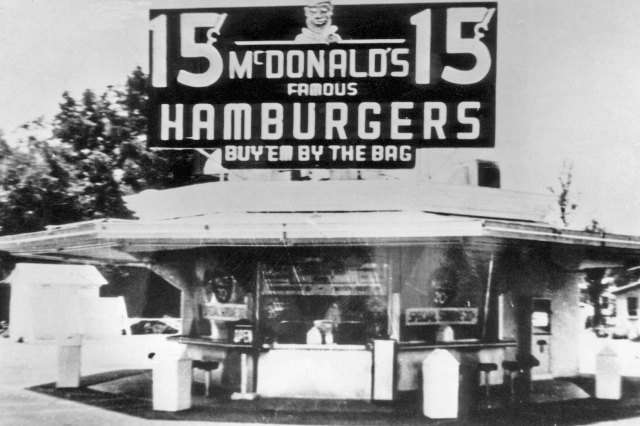

The idea of snacking has distinctly 20th-century origins. Eating between the traditional three meals per day was frowned upon during the 19th century, and proto-snack street foods of the time (such as boiled peanuts) were considered low class. But the Industrial Revolution, combined with a more enterprising spirit around the turn of the 20th century, created business opportunities for packaged, transportable foods, which were often marketed as novel expressions of modern technology.

As the nascent snack market emerged and grew, companies introduced countless products with varying degrees of success. Some, such as Cracker Jack (which debuted in 1896) and Oreos (which debuted in 1912 as a nearly exact imitation of the earlier Hydrox cookies), endure to this day. But history is littered with the wrappers of discontinued snacks. Here are some long-gone treats we’d love to see make a comeback.

Cherry Humps

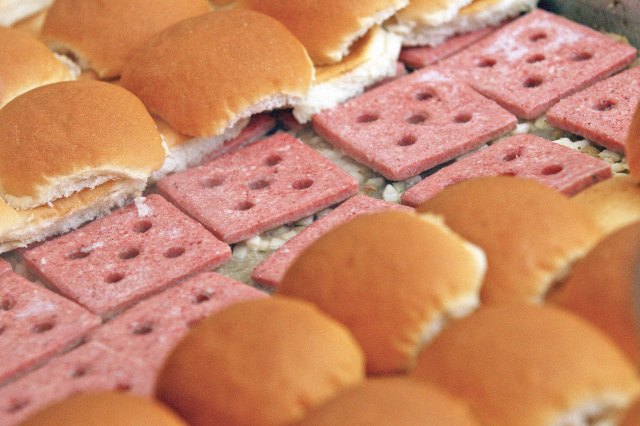

The Schuler Candy Company made this distinctive chocolate and cherry candy bar from 1913 to 1987. Each Cherry Hump bar contained two cherries, cordial, and fondant, and was double-coated in dark chocolate. In an unusual final step in their production, the bars were aged for six weeks, in order for the runny cordial and thicker fondant to meld and reach a cohesive state. Despite the cohesion achieved by aging, the filling of the candy bar still contained a more liquid texture than other candies, and this ended up being its undoing.

When Schuler became a subsidiary of Brock Candy Company in 1972, Brock sought to update the production and distribution methods of Cherry Humps, and chose bulky high-volume pallet shipments instead of the previous method of fanning out multiple shipments to smaller distribution lots. What made sense on paper for efficiency was disastrous in practice for a product as fragile as Cherry Humps: The candy often arrived at its destination badly damaged, with visibly sticky packaging from leaking cordial.

Instead of shoring up the candy’s packaging to protect it, or adjusting the shipping method, Brock changed the candy’s recipe to make it sturdier. The new recipe did away with the enticingly juicy cordial and fondant filling, instead setting firmer cherries in a layer of dense white nougat. There was no more gooeyness to speak of, and in turn, no more of the candy’s signature appeal. Sales steadily declined and Cherry Humps were discontinued.