How Were the Egyptian Pyramids Built?

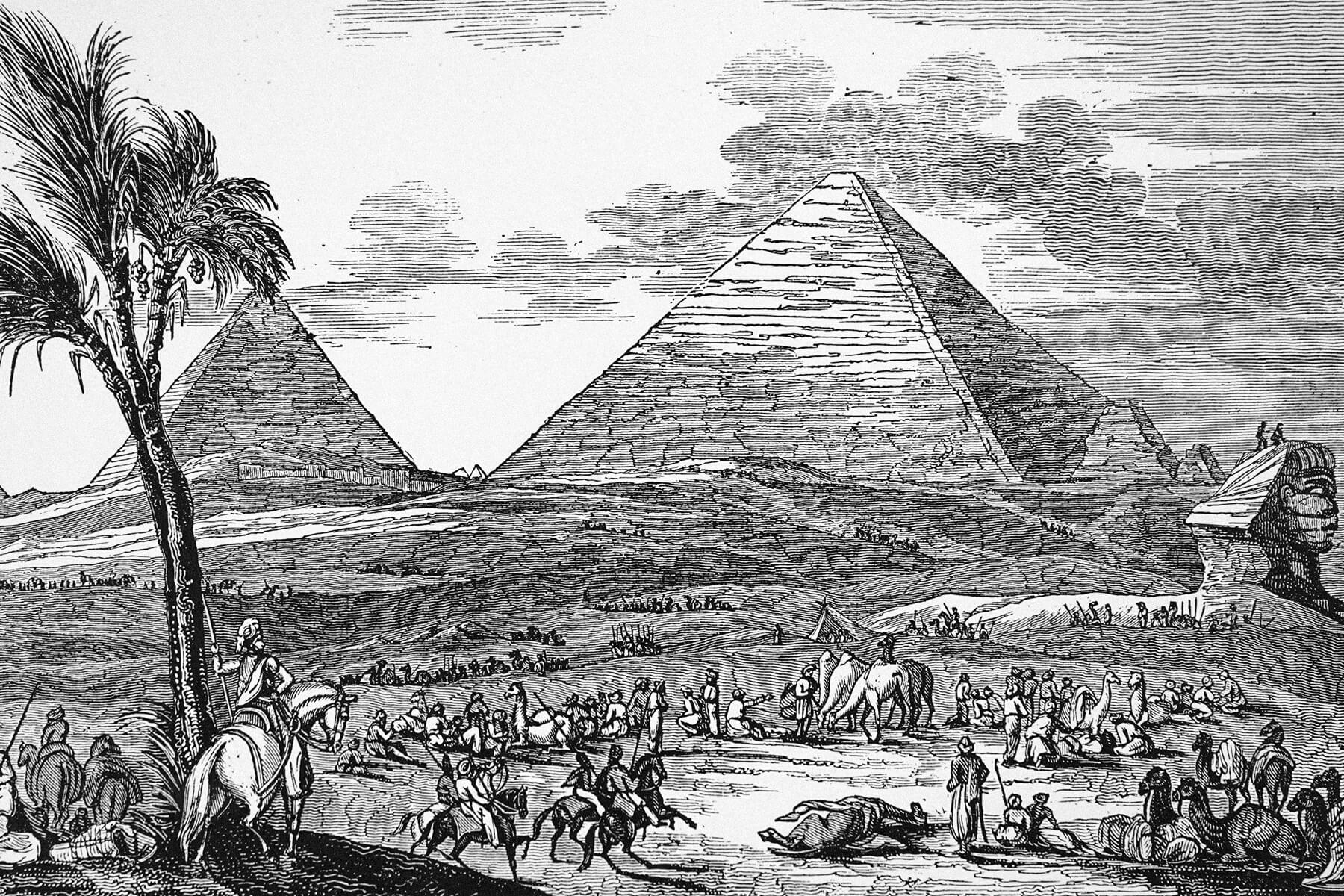

Ancient Egypt was home to more than 100 pyramids, many of which still stand today. One of the oldest monumental pyramids in Egypt, the Step Pyramid of Djoser, was built sometime between 2667 BCE and 2648 BCE and began a period of pyramid construction lasting more than a thousand years. The most famous monuments are found at the Giza complex, home to the Great Pyramid, the Pyramid of Khafre, and the Pyramid of Menkaure, all built during the Fourth Dynasty around 2600 to 2500 BCE — the golden age of ancient Egypt.

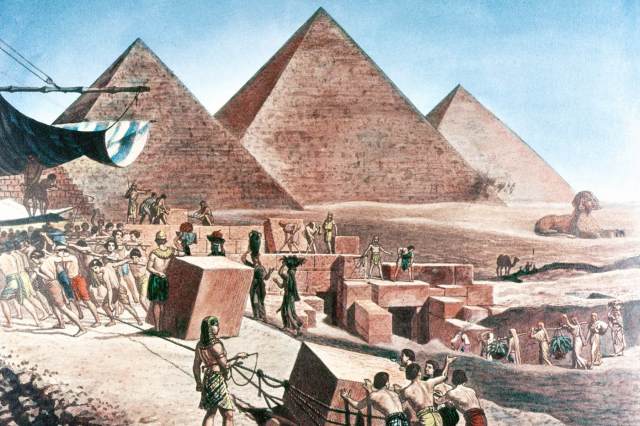

The Egyptian pyramids stand as one of humanity’s most remarkable architectural achievements, and their incredible precision and massive scale have confounded researchers for centuries. Despite numerous theories and extensive archaeological research, the exact methods of their construction remain a subject of scholarly debate. How did ancient Egyptians erect pyramids using millions of massive blocks weighing as much as 2.5 tons each? And how, more specifically, did they move those blocks up the superstructure?

To this day, there is no known historical or archaeological evidence that resolves the question definitively. While popular speculation often veers into fantastical explanations — yes, including aliens — serious historians and archaeologists have given much thought as to how these monumental structures might have been erected using the technological capabilities of the time. Here are three of the most likely construction theories.

The Herodotus Machine

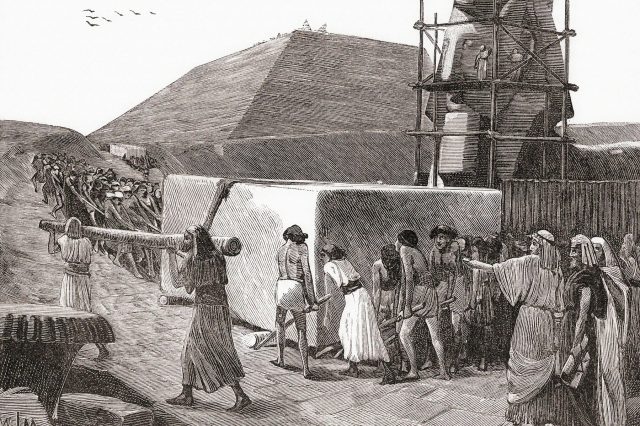

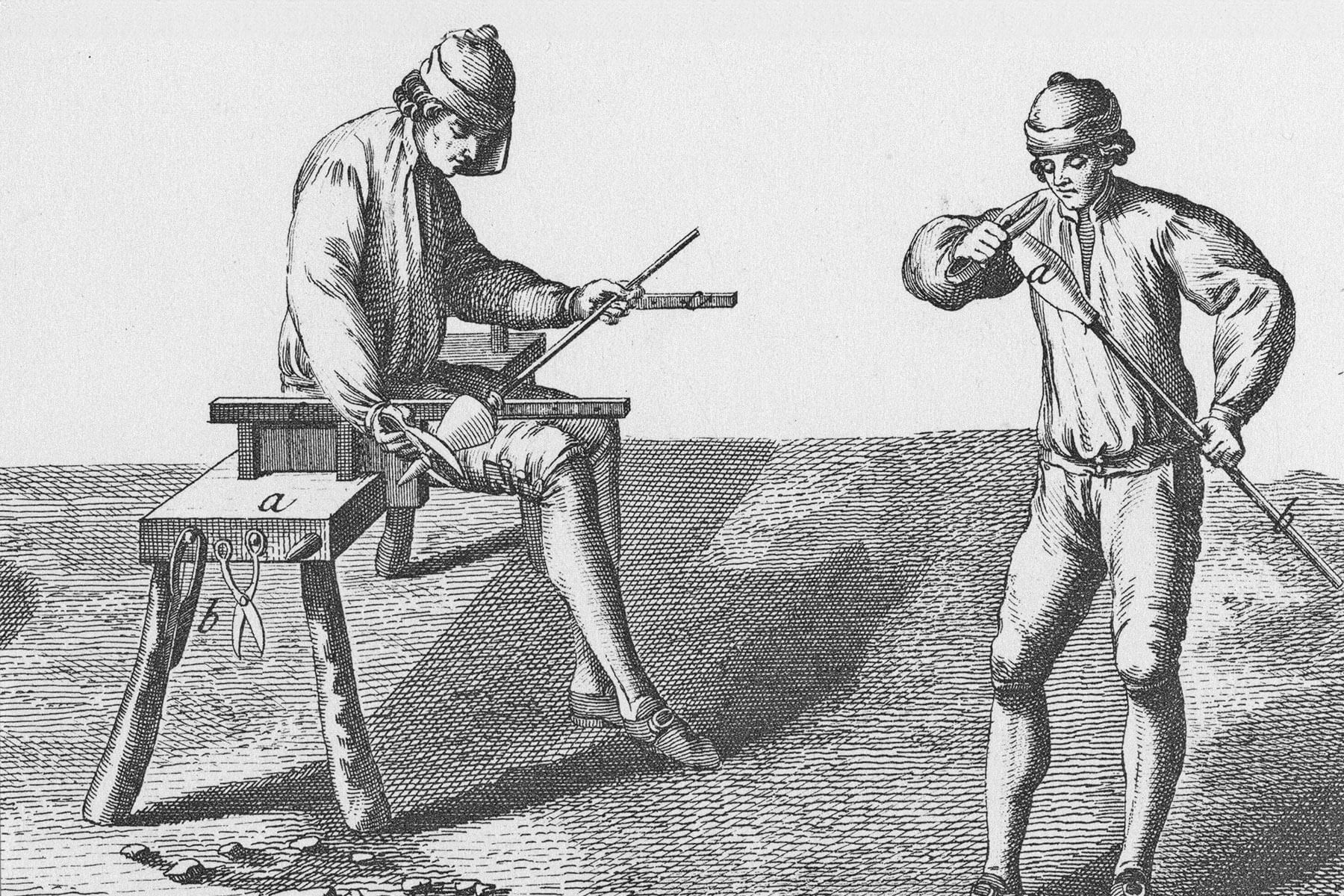

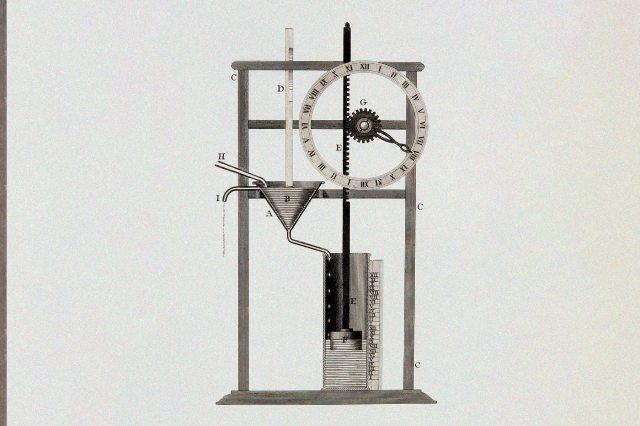

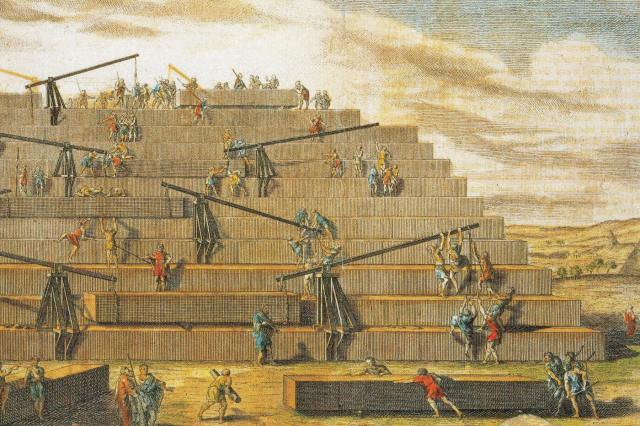

The first historical account of the construction of the pyramids came from the ancient Greek historian Herodotus in the fifth century BCE. In his Histories, he wrote that the Great Pyramid took 20 years to build and demanded the labor of 100,000 people. Herodotus also wrote that after laying the stones for the base, workers “raised the remaining stones to their places by means of machines formed of short wooden planks. The first machine raised them from the ground to the top of the first step. On this there was another machine, which received the stone upon its arrival and conveyed it to the second step,” and so on.

These “Herodotus Machines,” as they later became known, are speculated to have used a system of levers or ropes (or both) to lift blocks incrementally between levels of the pyramid. Egyptian priests told Herodotus about this system — but it’s important to note that this was a long time after the construction of the Great Pyramid, so neither the priests nor Herodotus were actual eyewitnesses to its construction. It is certainly feasible, however, that the machines he described may have been used, either by themselves or, more likely, in conjunction with other methods.