7 Items You Would Find in a Doctor’s Office 100 Years Ago

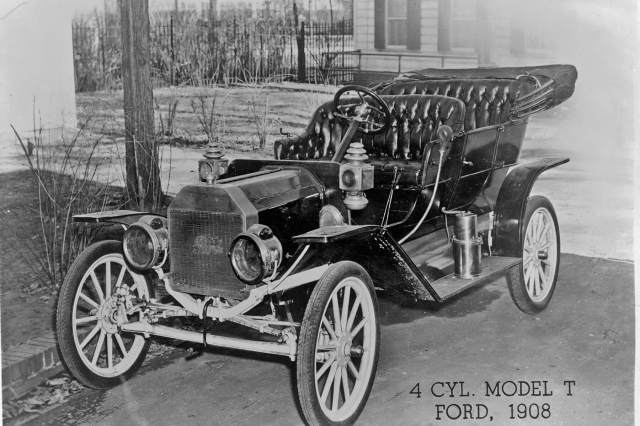

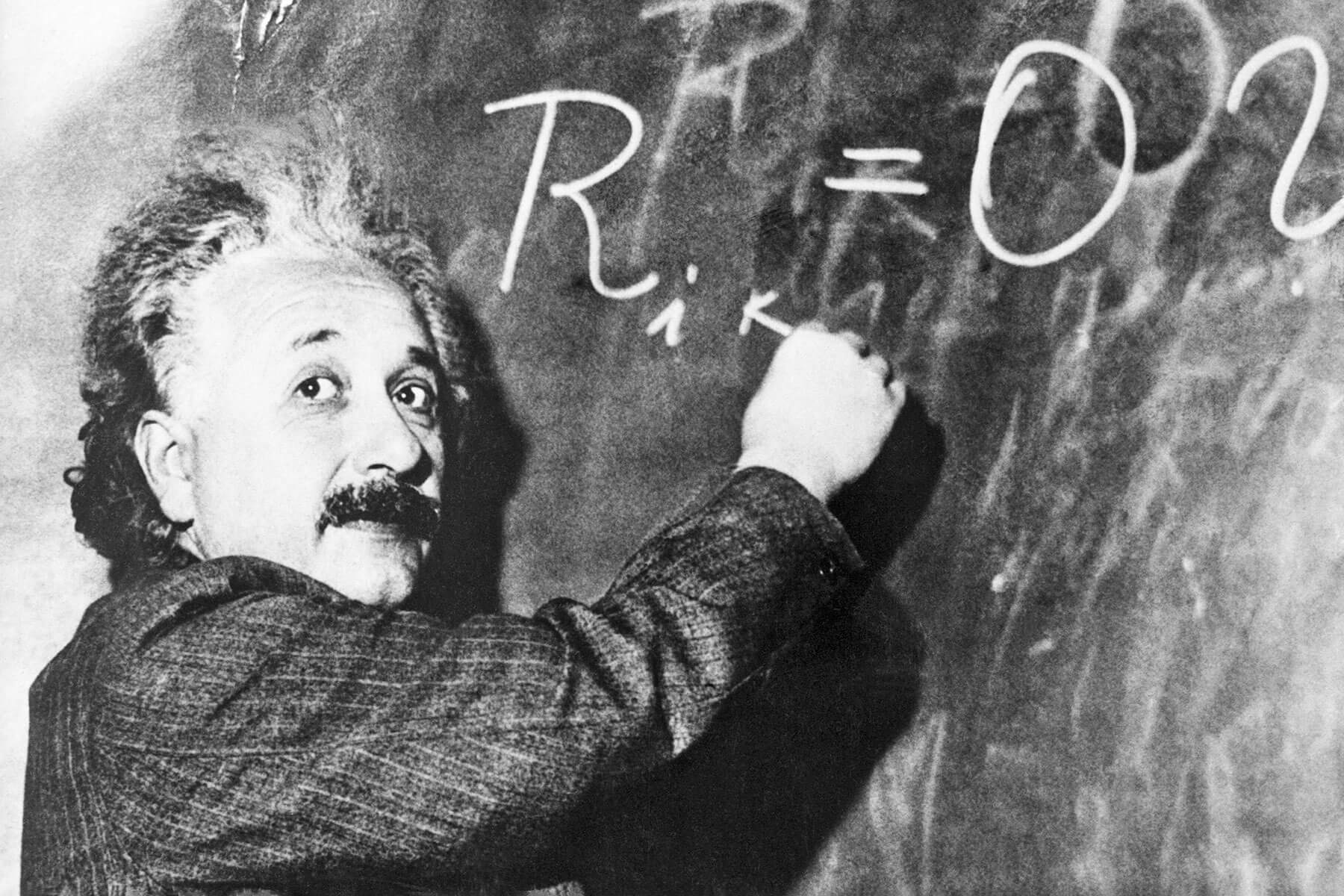

In many historical contexts, 100 years isn’t a very long time. But when it comes to science, technology, and medicine — particularly in the last century — it’s a veritable eternity. The seeds of modern medicine were just being planted in the early 20th century: Penicillin was discovered in 1928, physicians were still identifying vitamins, and insulin was a new breakthrough.

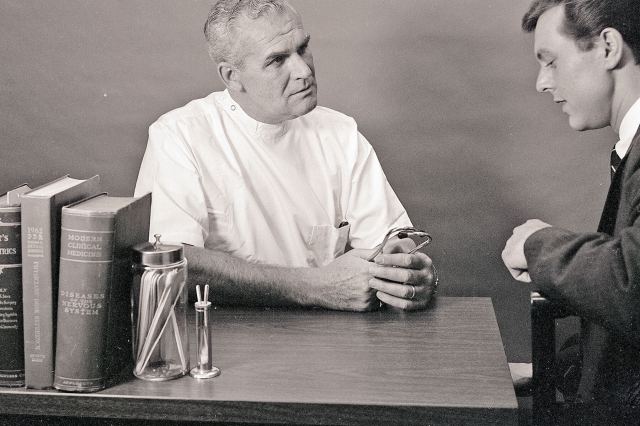

The doctor’s role itself was different than it is today, as preventative care was not yet an established practice; there was no such thing as a routine visit to a doctor’s office 100 years ago. A visit to the doctor typically meant that you were ailing (though in some cases during the Prohibition era, it meant that you and your doctor had agreed on a way around the alcohol ban). Thanks to advances in technology, doctors’ offices in the 1920s were also stocked with very different items than we see today. These are a few things you likely would have found there a century ago.

Head Mirror

A metallic disc attached to a headband is generally considered part of a classic doctor costume, but what is the genuine article, exactly? It’s called a head mirror, and your doctor 100 years ago would’ve been wearing one. It wasn’t just an emblem; it provided a very core function, which was illumination for the examination of the ear, nose, or throat. The patient would be seated next to a lamp that was pointed toward the doctor, and the head mirror would focus and reflect the light to the intended target. Today, the easier-to-use pen light or fiber optic headlamp have largely replaced the head mirror, though some ENT specialists argue that the lighter weight and cost-effectiveness of the latter mean it may still have a place in contemporary medicine.