6 Strange Things People Used To Do for Fun

Long before Netflix, video games, or podcasts existed, people turned toward other hobbies for their personal amusement — some of which seem quite strange by modern standards. Entertainment-seekers of yesteryear would gather to witness the unwrapping of ancient mummies, or pack arenas to watch people walk in circles for hours on end. These odd historical pastimes offer a fascinating glimpse into how folks in the past enjoyed their free time. Let’s take a look at six truly strange ways people used to have fun.

Mummy Unrollings

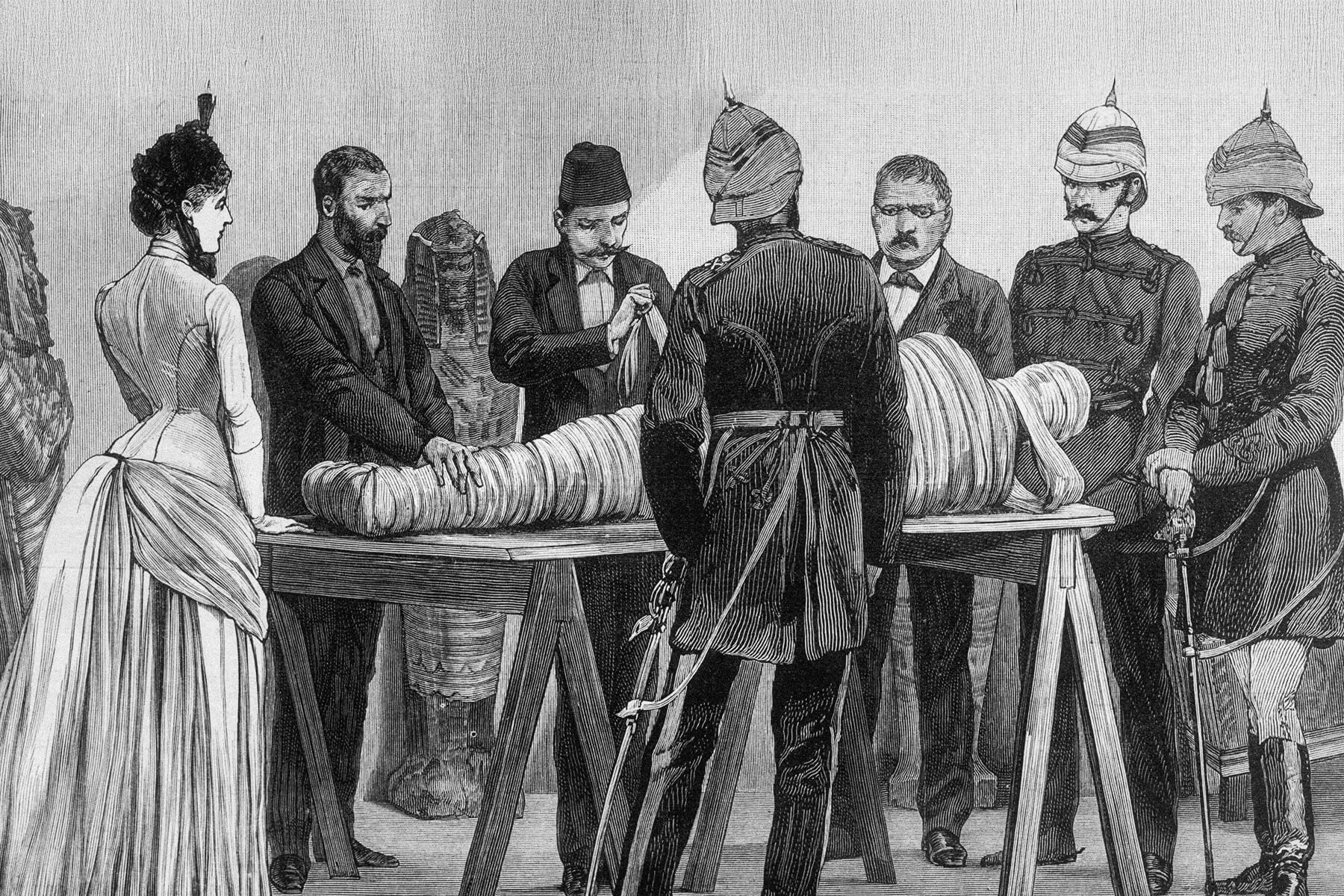

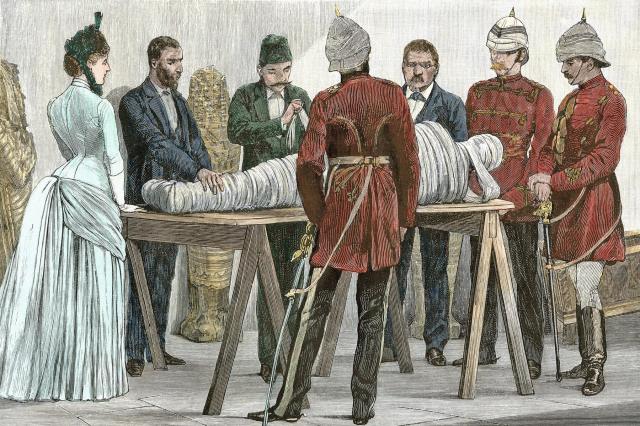

“Egyptomania” — a fascination with ancient Egyptian culture — swept across Europe in the 19th century, particularly in Victorian England, where people developed an obsession with mummies. It was even popular to attend events known as mummy unrollings, where actual corpses brought over from Egypt were unwrapped in the name of both science and morbid amusement.

In the middle of the 18th century, brothers and anatomists John and William Hunter were among the first to unroll mummies, doing so in the name of science. But the practice transitioned into more of a spectacle under enthusiasts such as “the Great Belzoni,” an explorer and showman who specialized in Egyptian antiquities, and Thomas “Mummy” Pettigrew, an English surgeon who was drawn to Egyptian antiquities. Pettigrew hosted private parties where he unwrapped and performed autopsies on mummies, revealing various amulets or bits of preserved hair and skin to the delight of those in attendance.

The trend really took off after the U.K. passed the 1832 Anatomy Act, which legally permitted doctors to dissect bodies for study. These mummy unrollings attracted large crowds, and were held at hospitals, scientific research centers, and private homes. The pastime remained popular for several decades, though ultimately lost its luster by the time Pettigrew died in 1865. Mummy unrollings continued, albeit on a smaller scale, with the last recorded event occurring in 1908.