The Top 25 History Facts of 2025

- Synchronized swimming, circa 1953

Author Bennett Kleinman

November 26, 2025

Love it?38

From the downright shocking to the utterly bizarre, some facts about history are particularly fascinating. Did you know the U.S. had a president before George Washington, or that Americans used to live inside giant tree stumps? If you missed these facts the first time, don’t worry — we’ve got you covered. Read on for the 25 most popular facts we sent on History Facts this year.

Twelve percent of the U.S. population served in World War II.

When Congress declared war on Japan on December 8, 1941, more Americans than ever before heard the call of duty. Some 16.1 million U.S. citizens served in the military by the time World War II ended in 1945, representing 12% of the total population of 132 million at the time.

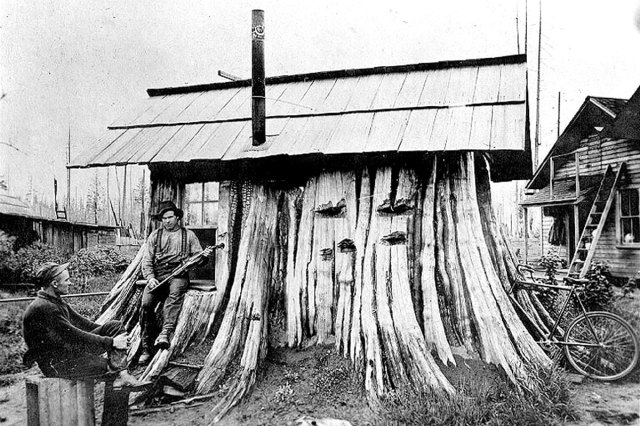

In the 1800s, some Americans lived inside massive tree stumps.

Before the logging industry, the trees in old-growth forests were hundreds of feet tall, with gnarled bases and trunks that could measure more than 20 feet across. To fell these forest giants, loggers would build platforms 10 to 12 feet off the ground, where the tree’s shape was smoother. The massive remaining stumps had soft wood interiors and sometimes even hollow areas, so it was relatively easy to carve out the center of a stump and turn it into a building, such as a barn, post office, or even the occasional home.

You may also like

More from our network

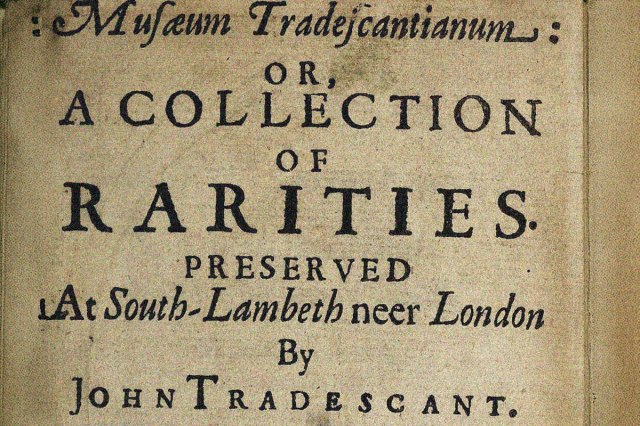

The British once sent a spy to China to steal secrets about tea.

In 1800, tea was the most popular drink among Brits — something of a problem for the British Empire, as all tea was produced in China at the time. And so the English did something at once sinister and cunning: They sent a botanist to steal tea seeds and bring them to India, a British colony at the time. One historian called it the “greatest single act of corporate espionage in history.”

Dwight D. Eisenhower’s road trip inspired the interstate highway system.

In 1919, Dwight D. Eisenhower, then a lieutenant colonel in the Tank Corps, learned of the U.S. Army’s plan to test the capabilities of its transport vehicles by moving 80 military vehicles across the country. After joining the expedition, he dutifully submitted a report analyzing the quality of the roads encountered along the way. Decades later, Ike made the development of America’s highways a centerpiece of his domestic agenda upon being elected U.S. president in 1952. His vision became the Interstate Highway System that crisscrosses the nation today.

“Teenagers” didn’t exist until the 20th century.

For most of human history, you were either a child or an adult. The word “teenager” first entered the lexicon in 1913, appropriately enough, but it wasn’t until decades later that it took on its current significance. Three developments in the mid-20th century had a major influence on the creation of the modern teenager: the move toward compulsory education, which got adolescents out of farms and factories and into high school; the economic boom that followed World War II; and the widespread adoption of cars among American families.

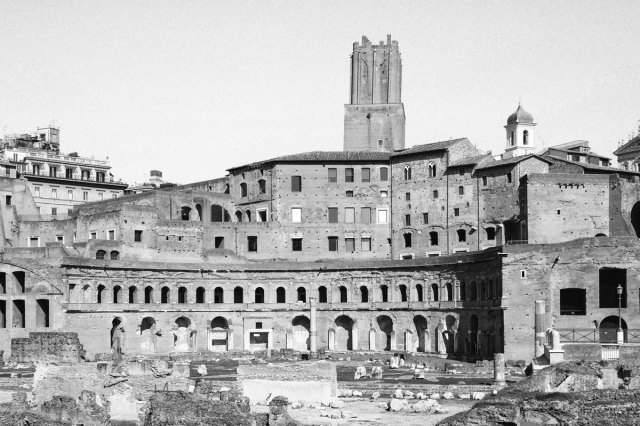

Ancient Romans used concrete more durable than modern concrete.

The ancient Romans are known for many innovations that were ahead of their time, and some that seem ahead of even our time. Case in point: Concrete used in some ancient Roman construction is much stronger than most modern concrete, surviving for millennia and getting stronger, not weaker, over time. The secret ingredient? The sea. Builders mixed this ancient mortar with a combination of volcanic ash, lime, and seawater, creating a material that essentially reinforced itself over time, especially in marine environments.

The U.S. had a “president” before George Washington.

Though George Washington is indisputably the first president of the United States, he technically wasn’t the first person in the federal government with the title of “president.” Washington was elected under the government formed by the ratification of the U.S. Constitution in 1788, but the Constitution wasn’t the only government-forming document in the nation’s history. Ratified in 1781, the Articles of Confederation — the United States’ first constitution — formed what’s known as the Confederation Congress. This early governing body was led by a president who held a one-year term, the first of whom was Samuel Huntington of Connecticut.

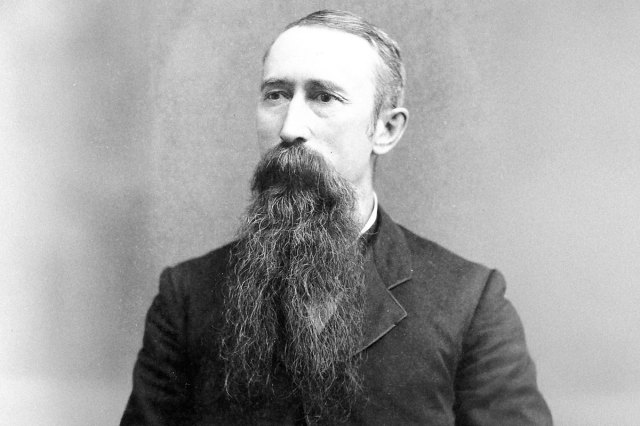

Victorian doctors prescribed beards for healthy throats.

The well-coiffed men of the Victorian era often had some truly impressive beards. The look was partially driven by the desire to appear manly and rugged, but beards were also seen as a way to ward off disease. At the time, many doctors endorsed the miasma theory of disease, which (incorrectly) held that illnesses such as cholera were caused by bad air. Facial hair, it was believed, could provide a natural filter against breathing in so-called “miasms.”

People hated shopping carts when they were invented in 1937.

When grocery owner Sylvan N. Goldman rolled out the first shopping carts in 1937, he expected a runaway hit. But the reaction wasn’t exactly enthusiastic. Women, already used to pushing strollers, weren’t eager to push another one at the store. Men, on the other hand, preferred not to push something stroller-like at all. Goldman even hired store greeters to hand shoppers a cart, and paid actors to walk around shopping with them until the idea finally caught on.

The world’s oldest bread is more than 8,000 years old.

The earliest loaf of bread ever discovered is a whopping 8,600 years old, unearthed at Çatalhöyük, a Neolithic settlement in what is now southern Turkey. While excavating the site, archaeologists found the remains of a large oven, and nearby, a round, organic, spongy residue among some barley, wheat, and pea seeds. After biologists scanned the substance with an electron microscope, they revealed that it was a very small loaf of uncooked bread.

The Pilgrims settled at Plymouth partly because they were running low on beer.

When the Mayflower passengers finally reached the shores of the New World, they spent a few weeks scouring the region for a spot to bunker down for the winter. As one passenger wrote in their journal, “[W]e could not now take time for further search or consideration, our victuals being much spent, especially our beer.” The Pilgrims promptly began building what became Plymouth Colony, with a brew house unsurprisingly among the first structures to be raised.

Baby Ruth bars weren’t officially named after the baseball player.

It’s easy to assume that Baby Ruth candy bars were named for the famed baseball player George Herman “Babe” Ruth Jr. Indeed, even the Great Bambino assumed as much at the time. After all, the nougaty confection debuted in 1921, after the ballplayer became a household name. But according to the official, legal explanation of the moniker, Baby Ruth bars were named after a different Ruth altogether: “Baby” Ruth Cleveland, the daughter of former U.S. President Grover Cleveland.

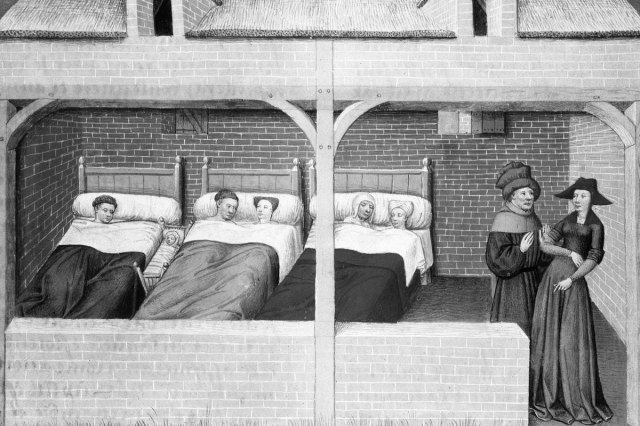

Medieval people sometimes slept in two shifts.

For the thousand or so years that encompassed the Middle Ages, people in Western Europe sometimes slept in two shifts: once for a few hours usually beginning between 9 p.m. and 11 p.m. and again from roughly 1 a.m. until dawn. The hours in between were a surprisingly productive time known as “the watch.” People would complete tasks and chores, check on any farm animals they were responsible for, and take time to socialize.

Birthdays weren’t always celebrated because few people even knew their birth date.

For most of human history, a birthday was just another day, and many people didn’t even know when theirs was. Ancient societies sometimes recorded births within noble or wealthy families, but systematic recordkeeping was rare. It wasn’t until the 1530s in England that churches were mandated to document baptisms. Similar practices appeared in colonial America, but birth registration didn't become widespread until the early 1900s.

During the Dust Bowl, some dust clouds reached as far as Boston, causing red snow.

The Dust Bowl wasn’t entirely confined to the Great Plains. Some of the dust storms that resulted from the natural disaster were so extreme that their clouds reached cities more than 1,500 miles away on the East Coast. Boston, Massachusetts, even saw red snow due to red clay soil becoming concentrated in the atmosphere.

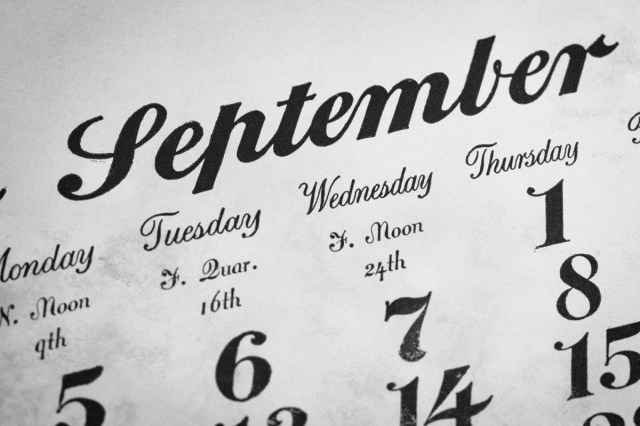

September was originally the seventh month of the year.

As you may expect, “sept” is a prefix with Latin roots that means “seven.” And indeed, the month of September was originally the seventh month in the Roman republican calendar. That calendar was used in ancient Rome for hundreds of years before the debut of the Julian calendar in 46 BCE. January and February joined the Julian calendar as the first and last month of the year, respectively, but nobody changed September’s name.

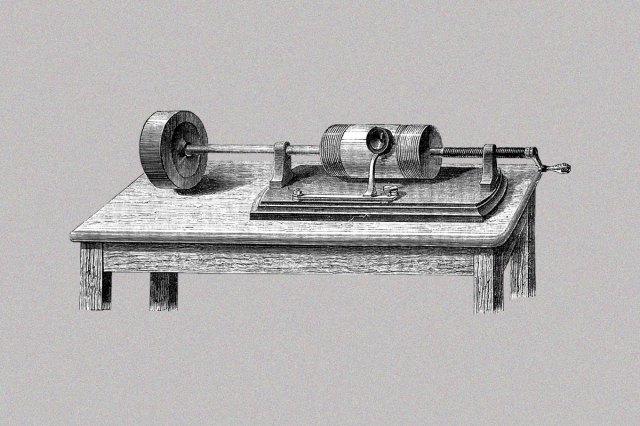

The oldest recording of a president is the voice of Benjamin Harrison.

We’ll never definitively know what presidents such as George Washington or Abraham Lincoln sounded like, since there are no audio recordings of their voices. The oldest existing recording of a U.S. president is the voice of Benjamin Harrison, the 23rd commander in chief, giving remarks at a diplomatic event. Harrison served from 1889 to 1893, and the audio recording dates to around his first year in office. His voice was captured on a wax cylinder phonograph, a recording device developed by Thomas Edison in the late 1880s.

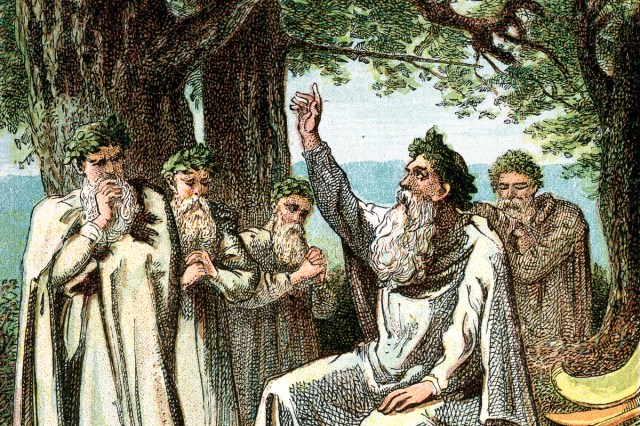

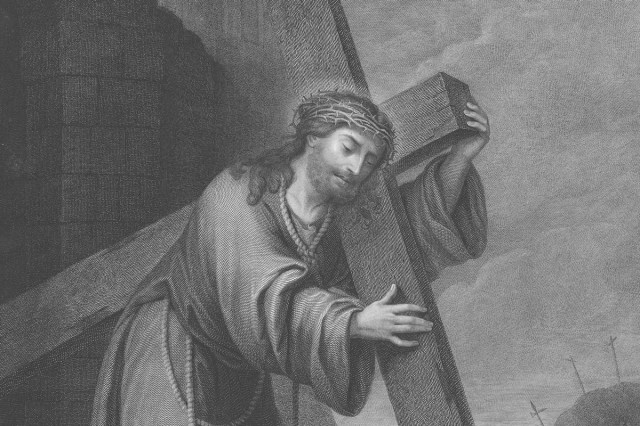

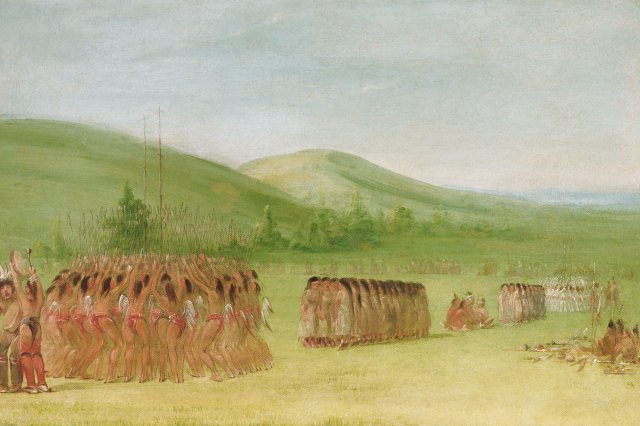

Synchronized swimming dates back to ancient Rome.

When you think of synchronized swimming, you may picture the glittering “aquamusicals” of the 1940s and ’50s. But the idea of choreographed aquatic performance actually dates back nearly two millennia — to the watery amphitheaters of ancient Rome. Roman rulers were obsessed with turning water into spectacle, even flooding the Colosseum to do so. The Roman poet Martial described a performance in which women portraying Nereids, or sea nymphs, dove and swam in formation across the Colosseum’s waters.

When rugs were too expensive, colonial Americans made sand art on their floors.

If you were a well-to-do family in colonial America, you may have draped your floor in richly painted oilcloth, or even imported carpets across the Atlantic. Most people, however, settled for simpler floor coverings, such as straw matting or sand. The latter came with a bonus feature: You could turn it into decor if you were feeling creative, drawing fun designs in the sand as a temporary decoration.

Edinburgh Castle is built on an extinct volcano.

Edinburgh Castle sits atop an imposing rock outcropping called Castle Rock. Ancient people started using the outcropping in the Bronze Age, and flattened its top around 900 BCE. But what they didn’t know is that hundreds of millions of years prior, that rock was the inside of a volcano. The volcano went dormant (and eventually extinct) roughly 340 million years ago, and the magma inside solidified, creating a rock formation that’s exceptionally sturdy and erosion-resistant — the perfect location for a stronghold.

The richest shipwreck ever holds around $18 billion in treasure.

When the San José first set sail in 1698, it probably wasn’t expecting to be making headlines three centuries later. The Spanish navy ship met its watery end off the coast of Cartagena, Colombia, with 200 tons of gold and emeralds aboard. Now known as the “holy grail” of shipwrecks, it’s presumed to be worth as much as $18 billion, which explains why several different entities have laid claim to the wreck since its discovery in the 1980s.

The practice of tipping dates back to the Middle Ages.

Though it’s often seen as a quintessentially American custom today, tipping has its roots in the feudal societies of medieval Europe. In the Middle Ages, wealthy landowners occasionally gave small sums of money to their servants or laborers for extra effort or good service. The gesture later evolved into a more formal custom: By England’s Tudor era, guests at aristocratic households were expected to offer “vails” to the household staff at the end of their stay.

China’s terra-cotta army was originally painted with vibrant colors.

The terra-cotta army in China is a collection of more than 7,000 life-size clay soldiers created in the third century BCE, each made with remarkable unique detail. But there used to be yet another layer of detail: Originally, these figures were painted in various vibrant colors. After the statues were sculpted, fired, and assembled, artisans applied lacquer (derived from a lacquer tree), followed by layers of paint made from cinnabar, malachite, azurite, bone, and other materials mixed with egg.

Handkerchiefs were once considered a status symbol.

Among the European aristocracy in the 16th and 17th centuries, especially in France and England, handkerchiefs were meant for display, whether in a pocket, a hand, or as part of an elaborate social ritual. These were no ordinary hankies; they were made with intricate lacework and fine embroidery. Wealthy Europeans posed for portraits with their hankies, bequeathed them in wills, and included them in dowries.

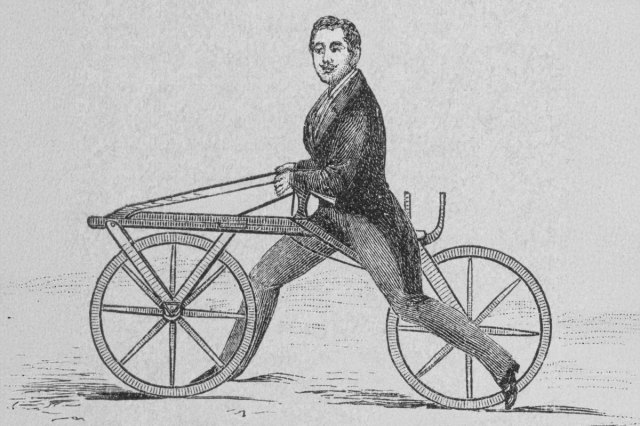

A volcanic eruption indirectly led to the invention of the bicycle.

In 1815, Mount Tambora in Indonesia erupted with extraordinary force. The fallout dimmed the sun worldwide, lowering temperatures and devastating harvests. As a result, food prices soared, and horses were slaughtered for meat or starved for lack of feed. This sudden scarcity of transport led to an innovation. In 1817, German inventor Baron Karl von Drais unveiled his Laufmaschine, or “running machine” — a simple two-wheeled wooden frame that riders straddled and propelled by pushing their feet along the ground. Like modern bicycles, it could travel far faster than walking, even on muddy post-rain roads.