What Ever Happened to the Milkman?

Grocery deliveries may be a modern convenience, but the service hearkens back to a bygone era when clinking glass bottles signaled the arrival of the milkman. The milkman (or milkwoman, though the job was usually held by men) is a cherished fixture of American history, as a prominent part of much of the 19th and 20th centuries. While milk remains a staple of the American diet, changes in consumerism and technology have made the once-ubiquitous milkman a relic of the past.

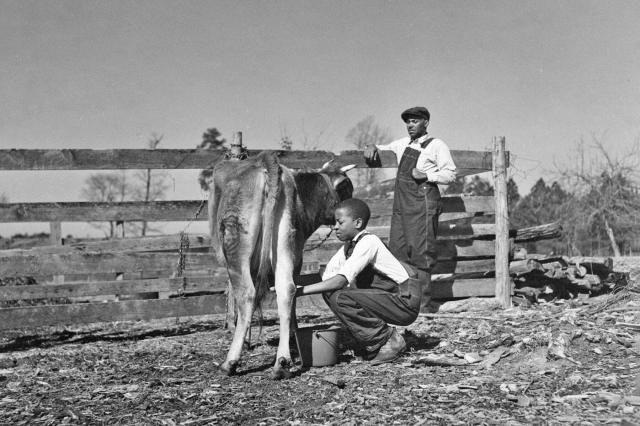

Cattle farming was a common means of sustenance in the early United States, beginning with the colonial era in the 16th century and continuing for the next few centuries. Many farming families produced milk, butter, and cheese for themselves and their local community. By the 19th century, the U.S. saw a rapid transformation due to industrialization and urbanization; people moved from rural areas to urban centers where better employment opportunities awaited. Owning a cow and making milk was much more impractical for these new city folk, but the demand for dairy remained.

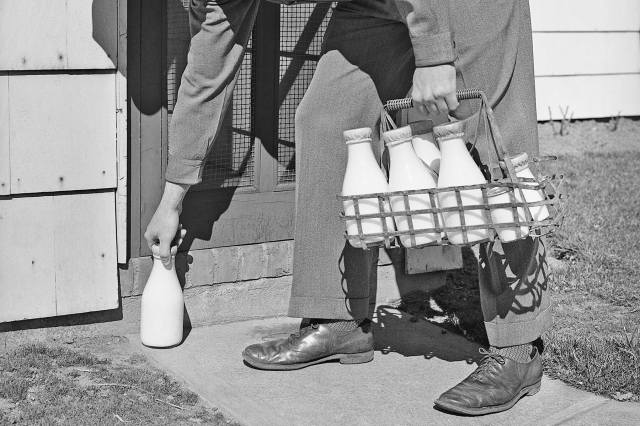

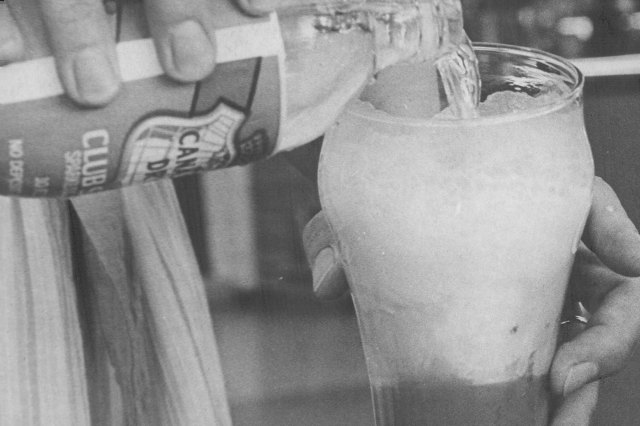

The concept of the milkman emerged around the late 18th century. The earliest providers filled large metal barrels with fresh milk right from the cow, carrying them by horse-drawn cart to customers’ homes. Milk was ladled into whatever containers were available, including pitchers, jugs, or pails. This often meant that the milk was contaminated by debris — anything from hair to dirt to insects. The advent of the now-iconic glass milk bottles in the late 19th century was a major advancement for both the convenience and the hygiene of milk delivery. Early bottles often had glass lids held on with metal clamps and were embossed with the name of the dairy that used them. Glass bottles were replaced by single-use, wax-coated containers in the 20th century, but to this day, glass milk bottles remain a niche, nostalgic emblem of another time.