5 of the Most Famous Telegrams in History

Although it still exists, the telegraph has been all but forgotten in a world dominated by instant digital messaging, relegated to the archives of 20th-century institutions alongside the corner phone booth and the horse and buggy. Yet there was a time when this form of communication was the best and most efficient way to deliver a message across significant distances. Western Union, the largest provider of the service, logged more than 200 million telegrams sent in its peak year of 1929.

Given the telegraph’s popularity, it’s not surprising that numerous important messages from the past two centuries traveled by way of telegram, some of which inspired notable changes to global events while others provided appropriate commentary to historic moments as they unfurled. Here are five such transmissions that have proved to possess staying power even as the technology that provided them has largely been pushed aside.

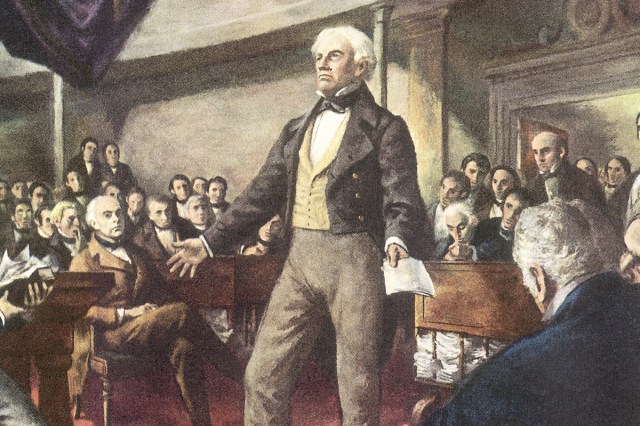

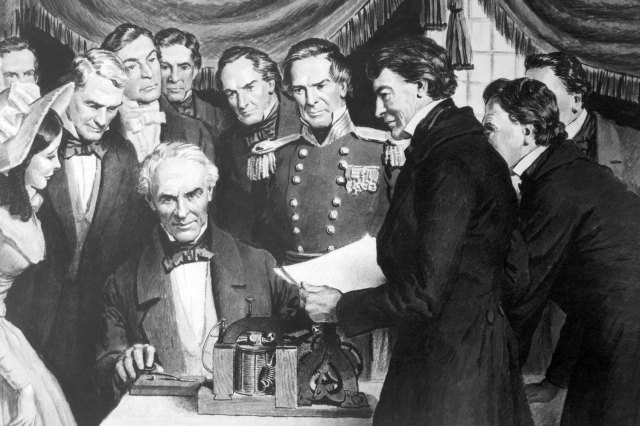

Samuel Morse’s Test Message From the U.S. Capitol

On May 24, 1844, some 12 years after he set about devising a way to transmit information by way of an electrical current, Samuel F.B. Morse prepared to showcase his perfected invention before an influential audience in the U.S. Capitol. Morse transmitted the words “What hath God wrought” — a message inspired by the Bible, suggested by the patent commissioner’s daughter — over a copper wire that followed the B&O Railroad line nearly 40 miles to a Baltimore station. There, his assistant Alfred Vail received the message and replied with the same phrase from a second machine.

This wasn’t the first example of a working telegraph. Inventors William F. Cooke and Charles Wheatstone had unveiled their version in the United Kingdom in 1837, and Morse and his team had previously conducted demonstrations across shorter distances. However, this particular showing, colored by a message hinting at divine intervention, has endured as the impetus for the rapid spread of this novel communication system over the following decade.