What Did History’s Most Important Moments Smell Like?

Think about the historical moments you’ve learned about over the course of your life — scenes shaped by textbook descriptions, famous photographs, paintings, or old newsreels. Some historical events left tangible evidence behind: documents, tools, clothing, buildings, and personal objects that help anchor those happenings in the real world. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, many of history’s turning points were even documented with sound, preserved on scratchy recordings or early film.

But there’s one sense that we rarely consider when talking about the past: what history smelled like. It’s not something most of us have considered because it’s not usually possible to bottle or archive an odor from the past. Still, the historical moments that we know so much else about had distinct smells shaped by their environment. When we pause to imagine the smell of pivotal events, history becomes less distant and more immediate. Here’s what some of the most important moments in history likely smelled like.

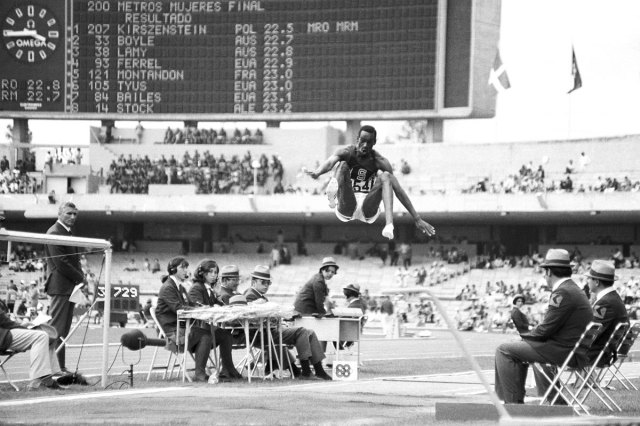

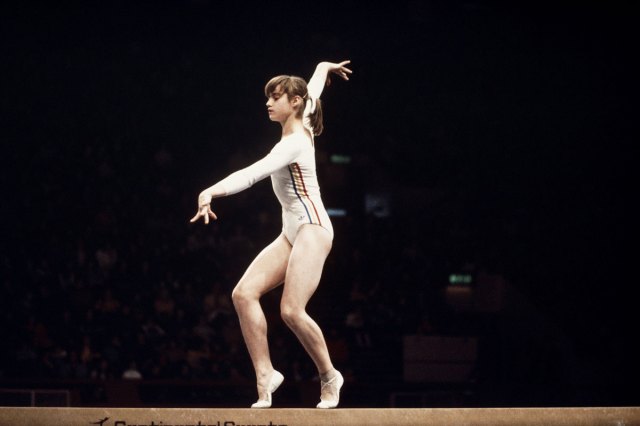

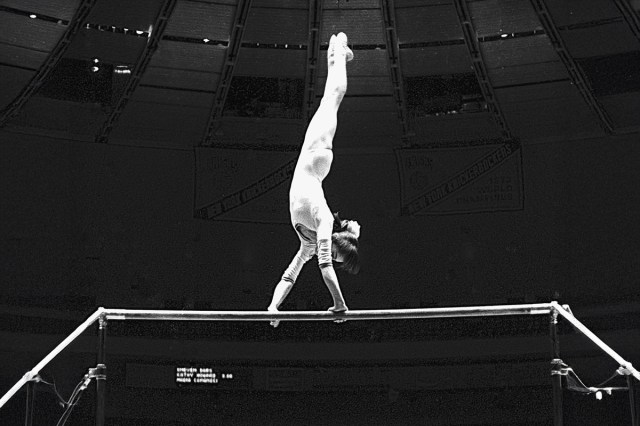

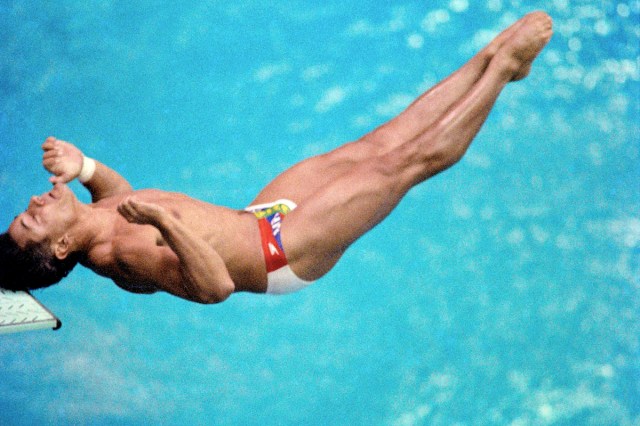

The First Olympic Games (776 BCE)

The first recorded Olympic Games, held at Olympia, Greece, in 776 BCE, unfolded in air thick with oil, dust, and body odor. Athletes often competed nude with their bodies massaged and coated in olive oil that smelled fresh, grassy, and faintly bitter, clinging to skin warmed by the sun. Mixed with this was the sharp, salty odor of sweat from unwashed bodies, intensified by days of exertion, heat, and close proximity in training and competition areas, where physical contact further concentrated these smells.

Underfoot, dry earth and trampled grass released dusty, mineral scents as crowds moved through the grounds. Animal dung from pack animals, human waste in nearby latrines, and food scraps added to the odors. Herbal garlands of laurel, thyme, and wildflowers contributed pleasant aromas, while animal sacrifices to Zeus created a heavy odor of greasy smoke and charred meat that lingered throughout the area. It was a smell of dedication and competition, marking the Olympics as both a religious festival and a test of physical excellence.