Did People in Ancient Rome Really Wear Togas?

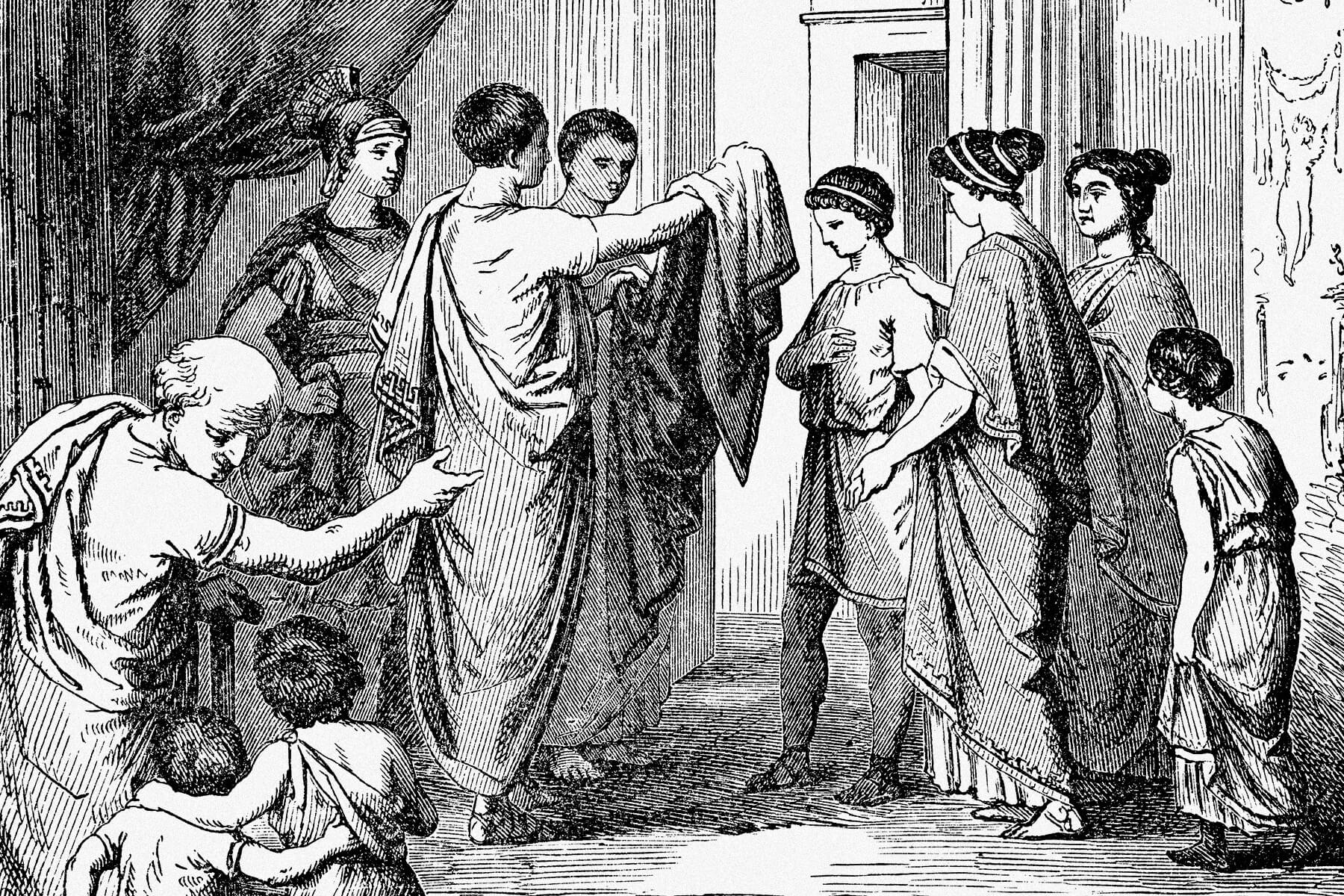

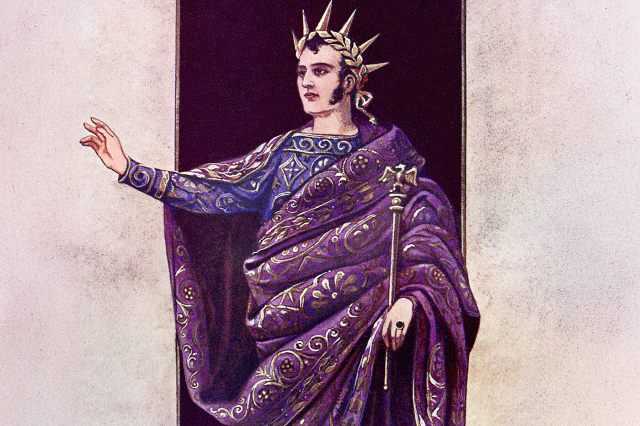

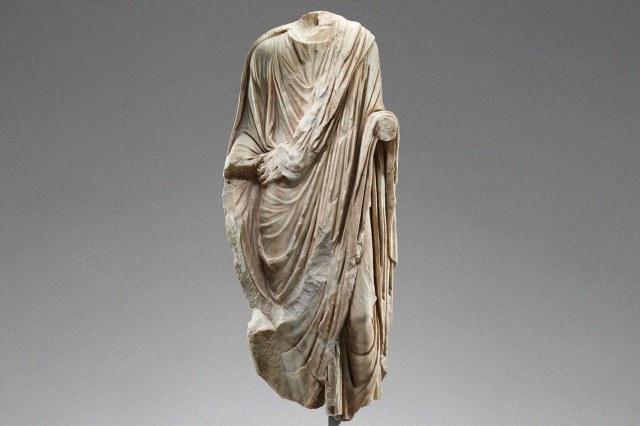

When we think of ancient Rome, we often think of the toga, generally depicted as a flowing white garment arranged in folds around the body and typically worn over a tunic by senators, philosophers, and citizens in grand marble forums. It’s an image that has persisted for thousands of years and has been reinforced in mythology and history. In the epic poem “Aeneid,” the Roman poet Virgil refers to Romans as “masters of the world, and people of the toga.” And in Roman folklore, Romulus — the founder of Rome — is depicted wearing a toga.

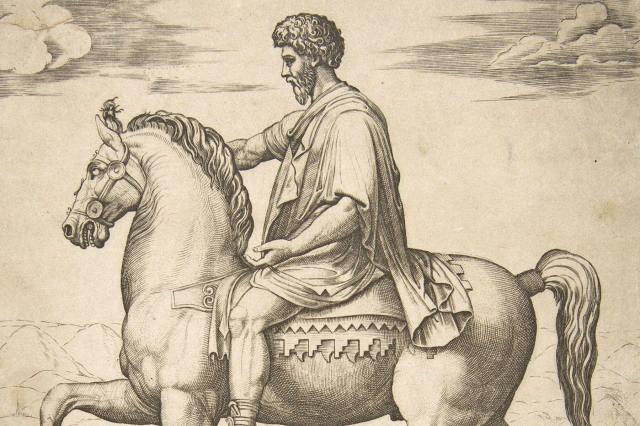

To ancient Romans, the toga represented a symbol of citizenship, status, and identity — and not everyone was entitled to wear it. The evolution of the garment spans centuries and came to symbolize Roman culture and values. As Rome changed, so did its fashion, but the toga remains a lasting image of a civilization that shaped the Western world.

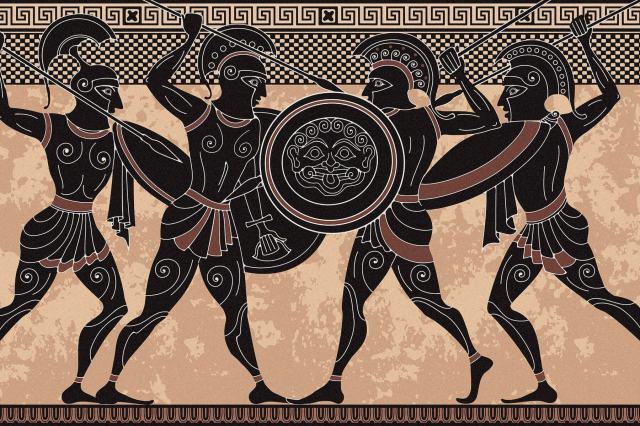

Romans Weren’t the First To Wear Togas

While the toga is quintessentially Roman, similar garments existed in other ancient cultures. The Greeks wore the himation, a large rectangular cloth draped over the body like a cloak. While less structured than the toga, it also served as a marker of status and decorum. The Etruscans, another ancient Italian society whose culture greatly influenced the Romans, wore the tebenna, a garment resembling the toga that didn’t carry any particular symbolic associations.

What set the Roman toga apart was its evolution into a distinctly Roman symbol. The toga became a visual marker of Roman citizenship, distinguishing Romans from the diverse peoples they ruled, and remained a symbol of Rome long after it fell out of fashion. Roman dress borrowed and incorporated elements from other cultures in the empire, resulting in a variety of toga styles and colors over the centuries that reflected the diversity of the Roman Empire.