5 Little-Known Facts About the Berlin Wall

As tensions rose between the Soviet Union and the West after World War II, Soviet Prime Minister Nikita Khrushchev sought to end the wave of emigration out of the USSR-controlled East Germany. The number of fleeing East Germans was staggering: Between 1949 and 1961, roughly 2.5 million people fled the state, a loss that threatened to upend the East German economy. Finally, after upwards of 65,000 citizens migrated to West Berlin between June and August 1961, East German leaders pushed for Moscow to close the border, and construction of the Berlin Wall began the night of August 12, 1961.

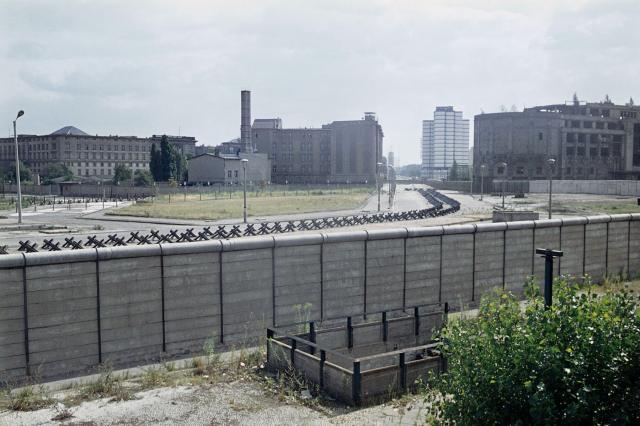

The boundary started off as a barricaded barbed wire between East and West Berlin, and the effects were swift and merciless. Within two weeks, the border to the west was completely sealed — crossing was forbidden, and the wall was guarded by officers permitted to shoot attempted escapees on sight. For the next two decades, the now-infamous barrier served as a symbol of the political and ideological divide of the Cold War. Here are five interesting facts about this notorious structure.

The Name “Checkpoint Charlie” Came From the NATO Phonetic Alphabet

Berlin was divided into four sectors following the Second World War. The Soviet Union controlled the eastern part of the city, while France, the United States, and Britain controlled three sectors in the west. There were three major checkpoints along the Berlin Wall, which monitored the border crossings of foreigners, diplomats, and military officials: Checkpoint Alpha, Checkpoint Bravo, and the most famous, Checkpoint Charlie. The names of all three checkpoints originated with the NATO phonetic alphabet, representing the letters “A,” “B,” and “C.” Checkpoint Charlie was located in the heart of Berlin, and marked the divide between the Soviet and American zones. It became a symbol of the Cold War divisions, and is now a historical site and memorial in Berlin.