Why Do Clocks Move Clockwise?

If you grew up with an analog clock on the wall, you might remember learning that the “little hand” marked the hour and the “big hand” showed the minutes. And you probably never questioned why the hands moved in a particular direction — they simply turned “clockwise.”

But the familiar movement of a clock’s hands is a human invention influenced by geography and centuries of history. To understand why clocks move the direction they do, we have to look back to a time before clockmakers designed the gears and pendulums of our analog clocks — back to when people first started watching and recording the sun’s slow, predictable arc across the sky.

The Sun Set the Standard

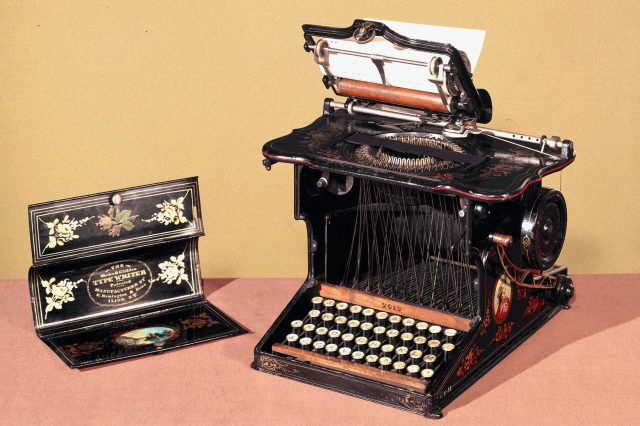

Long before mechanical clocks existed, people measured time by watching shadows. The earliest timekeeping tools — such as a simple vertical stick called a gnomon — were used in places such as ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia to track the sun’s movement.

In the Northern Hemisphere, the sun rises in the east, arcs across the southern sky, and sets in the west. As the sun moves, the shadow cast by a gnomon shifts in a predictable path: facing west in the morning, north around noon, and east in the evening.

However, the direction of movement depends on the type of sundial. On a horizontal sundial, the kind most familiar in Europe, the shadow moves in the same direction as the hands on a modern clock. On vertical, south-facing sundials, or at different latitudes, the shadow can move in the opposite direction, and its path changes slightly with the seasons. In the Southern Hemisphere, where the sun arcs across the northern sky, many sundials naturally produce what we would call a “counterclockwise” motion.

But mechanical clocks were first developed in regions where horizontal dials were common, and shadows created a consistent pattern as the sun moved east to west. This visual rhythm became the template for future timekeeping. When early European clockmakers began building mechanical clocks, they chose to replicate the familiar motion of the sundial shadow. That choice fixed the direction that became known as “clockwise.”