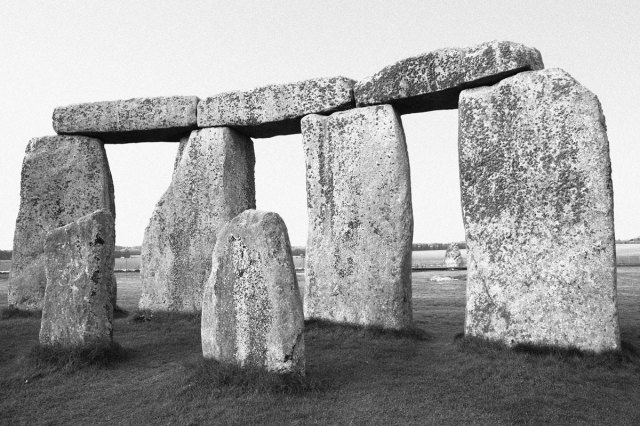

What Was Stonehenge’s Actual Purpose?

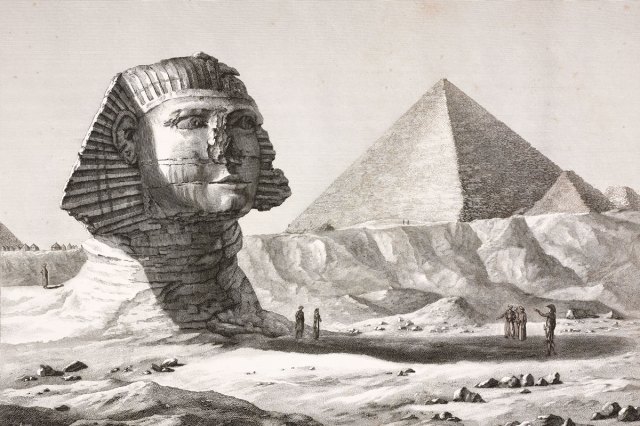

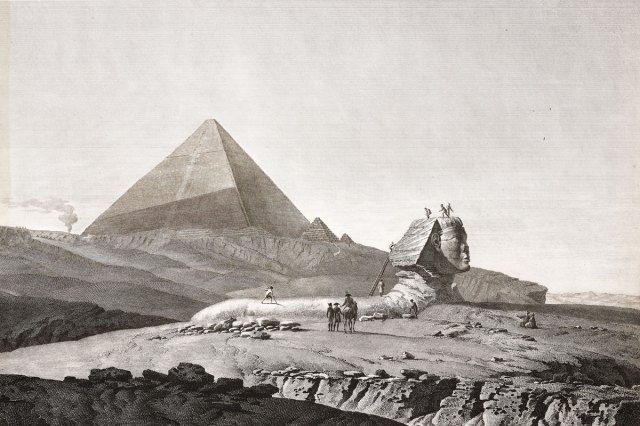

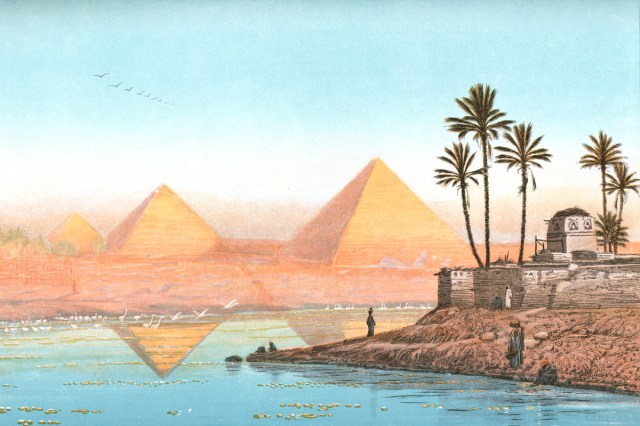

For thousands of years, Stonehenge has stood on England’s Salisbury Plain, shrouded in mist and mystery, its massive stones arranged in circles that continue to puzzle archaeologists and visitors alike. Built around 4,500 years ago — around the same time as the Sphinx and the Great Pyramid of Giza in Egypt — this historic monument has inspired many theories as to its purpose. Was it an ancient observatory? A burial ground? Or something else entirely?

As Stonehenge was built by a Neolithic culture that left no written records, little is known for sure about its origins. The first significant surveys and excavations of the monument were made by English antiquarians John Aubrey and William Stukeley in the late 1600s, and it was they who first suggested the Druids as the most likely engineers — a myth that stuck (and is widely repeated even today), despite Stonehenge predating the Druids by more than a thousand years. People have studied the site ever since and further discoveries are still being made, expanding our knowledge regarding who exactly may have built Stonehenge and why. And recent research suggests its purpose was more complex than anyone imagined.

An Astronomical Calendar

The idea of Stonehenge as an astronomical observatory has been around for a long time. As far back as the late 18th century, the antiquarian and polymath James Douglas concluded that the monument must have been an ancient solar temple due to its alignment with the midsummer sunrise. The theory of Stonehenge as some kind of Neolithic calendar gained traction from there, prompting many similar studies, including research in the 1960s when computers were used to make more precise calculations.

Archaeological studies have proved that solstitial alignment was almost certainly a consideration of the people who built Stonehenge. It appears, however, that marking the summer solstice was not the priority. Due to the form and layout of Stonehenge, many archaeologists now believe that midwinter was the more important marker — which makes sense given that winter was the most challenging time of year for ancient agricultural communities.