People thought trains would cause “railway madmen.”

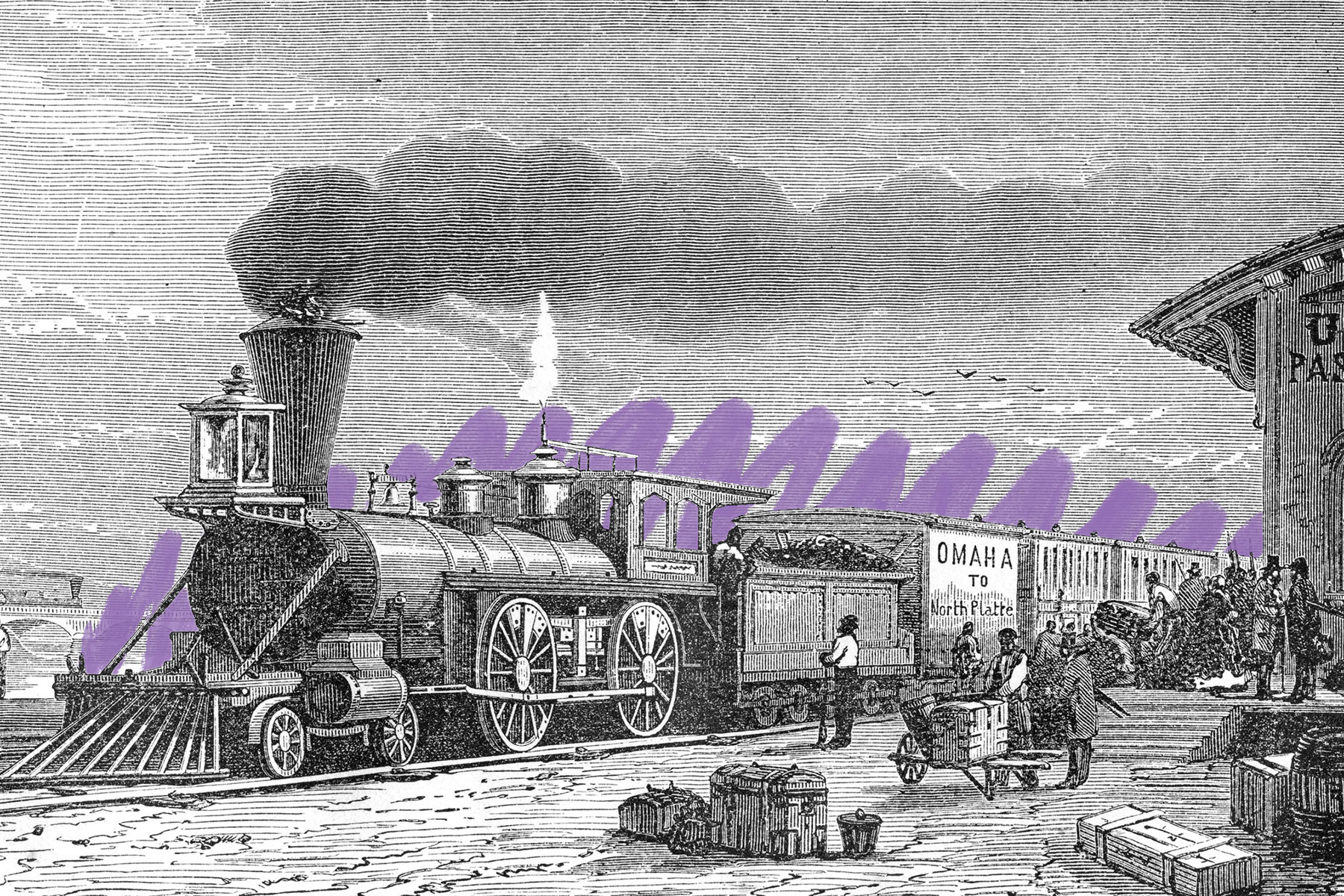

During the Victorian era, rail travel was instrumental in England’s rapid transformation from an agrarian culture to an urban, industrialized society. It generally improved life for a large segment of society, leading to new opportunities in travel, transporting goods, business development, and the growth of towns and cities. But flaws in the fledgling railway system posed both minor and major dangers. Only first-class passengers enjoyed the luxury of windows, and third-class carriages did not have roofs until 1844. More seriously, most railway carriages were unlit and had no aisles, making passengers vulnerable to a variety of criminals, from pickpockets to con artists.

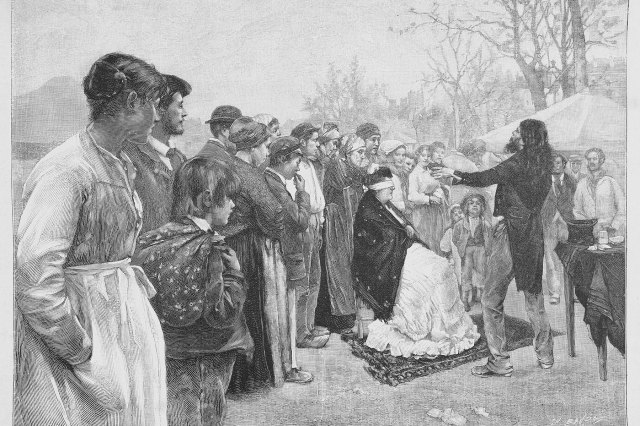

Another perceived threat to public safety was the rise of the “railway madman.” An 1864 New York Times article entitled “A Madman in a Railway Carriage” warned readers of a train passenger who seemingly had a mental breakdown once the train began moving. He accused other riders of stealing from him and eventually attempted to jump out of the moving train, requiring his fellow passengers to strap him to his seat for the rest of the journey. Even though the article mentioned that onlookers believed the man to be suffering from a “violent attack of delirium tremens,” a slew of sensational newspaper pieces from other outlets led readers to believe that England was beset by an epidemic of “railway madmen” caused by traveling at high speeds. Some physicians warned that the jolts and bumps of frequent train riding could cause brain damage, leading some to lose their minds, and medical journals discussed finding methods for identifying a latent “railway madman” before he struck. Ultimately, the phenomenon faded from the collective consciousness as inexplicably as it began. Though scattered attacks and incidents continued to be reported sporadically over the next few decades, the panic faded, and train travel became a staple of modern life.