Archery used to be required by law for English men.

Throughout the Middle Ages, English men were required by law to practice longbow archery — a mandate that was in place for longer than you might expect. Early laws encouraged practicing archery indirectly: King Henry I, who ruled England from 1100 to 1135, declared that deaths accidentally caused by practicing archers didn’t count as murder or manslaughter. During the reign of Henry III, the 1252 Assize of Arms required that able-bodied men of a certain means between the ages of 15 and 60 be equipped with a bow and arrows and know how to use them — although residents of England’s royal forests had to practice with blunt arrows to protect the king’s game.

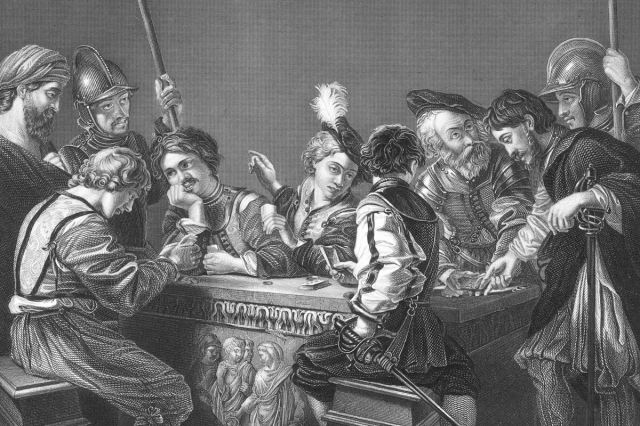

In 1363, King Edward III, who was in the midst of the Hundred Years’ War and convinced that archery skills were “almost wholly disused,” declared that able-bodied men must practice archery on holidays. The Archery Law, enacted that same year, further demanded practice on Sundays. Edward also outlawed, on pain of imprisonment, watching or participating in “vain games of no value,” a wide net that included handball, football, hurling stones, and cockfighting.

Subsequent kings laid down similar acts: Richard II banned several games and required serfs and peasants to practice the longbow, and Edward IV set minimum imports for equipment. Henry VIII, after introducing several bans on games and tighter enforcement procedures earlier in his reign, passed one of the most notorious pro-archery laws of all in 1541: It nullified all previous acts, banned even more non-archery sports, and exempted wealthy people. In addition to requiring men under 60 (and, to a lesser extent, their male children) to own a certain amount of archery equipment, it empowered employers to garnish the wages of any servants who didn’t have it. The 1541 law was still on the books in bits and pieces until the 20th century, but England’s Betting and Gaming Act of 1960 finally nullified the last of the country’s longbow mandates.