What Exactly Is Feudalism?

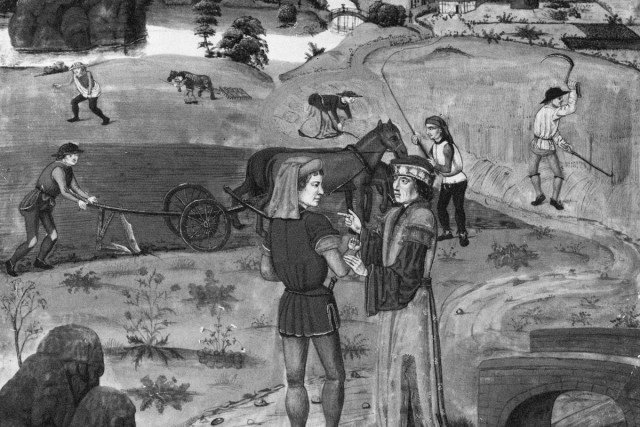

The concept of feudalism is probably a familiar one if you’ve encountered a medieval fantasy epic: Picture a stone castle overlooking fields of peasants tilling the soil while armored knights ride out at dawn. But what does the term actually mean, and how did feudalism work in practice?

Feudalism is a term used to describe how power, land, and obligation were organized in much of medieval Europe. At its core, it refers to a system in which land was the main source of wealth and political authority, and control of that land was tied to personal relationships of loyalty and service.

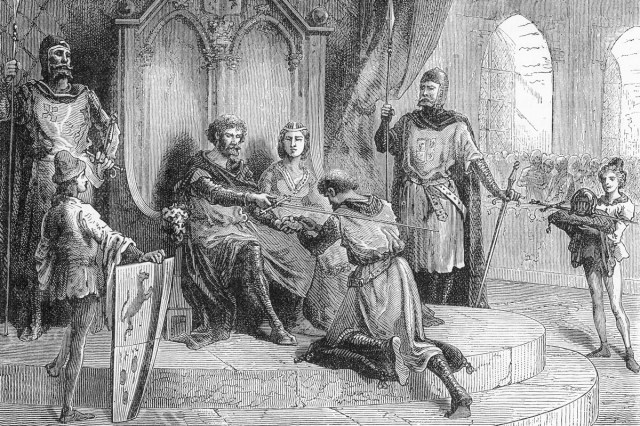

In this arrangement, a monarch was considered the ultimate owner of all the land in their kingdom. The ruler granted large estates, called fiefdoms, to nobles in exchange for allegiance and military support. Those nobles could then distribute portions of their land to lesser nobles (such as knights), creating a layered hierarchy of obligation known as vassalage.

At the bottom of this structure were peasants and serfs, who worked the land and provided labor or goods in return for protection and the right to live on the estate. Power was exercised largely at the local level, rather than through a strong centralized government. For instance, a king might grant land to a duke, the duke to a knight, and the knight would then draw income and labor from the peasants who worked that land, creating a chain of obligation that ran downward while authority flowed upward.

It Started With the Fall of Rome

Europe’s feudal structure developed gradually in the centuries after the collapse of the Western Roman Empire around 476 CE. As Roman authority weakened, Western Europe experienced political fragmentation and repeated invasions by Germanic peoples, whose social structures emphasized personal loyalty to a leader rather than obedience to the laws of a centralized state.

Over time, Roman legal traditions blended with Germanic customs centered on allegiance and service. In an era marked by resource insecurity, warfare, and limited state power, people increasingly turned to powerful local lords for protection. In return, they offered these lords labor, military service, or political loyalty, reinforcing the link between landholding and authority.