The Curious History of the Piggy Bank

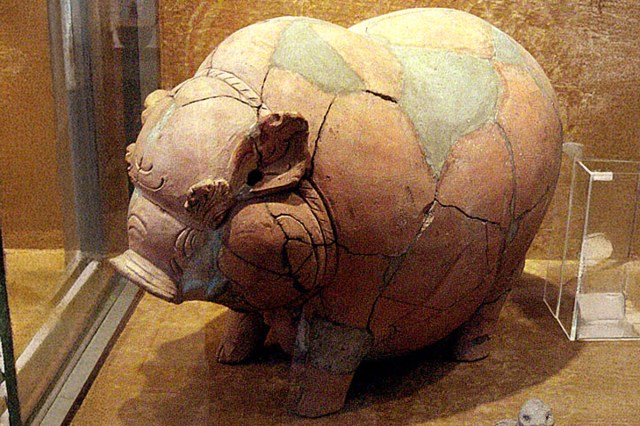

If you’ve ever dropped spare change into a rotund, smiling, ceramic pig, you may have wondered: Why a pig? The idea of putting coins inside a chubby farm animal may seem whimsical, but the story of how pigs became the symbol of savings reaches back further than you might expect — and the real explanation busts a common myth that’s been circulating since the 1990s.

Pigs as the Original Savings Account

Before there were coin jars, there were pigs — real ones. In modest households across Europe, pigs were literal stores of value. A piglet bought in spring could be fattened on kitchen scraps and garden waste and, come winter, would provide both food and money. As the Bank of Canada Museum puts it, “A pig — a real one — is an excellent store of value.” In many rural communities, a family’s pig was essentially its bank: a source of meat, trade goods, or emergency cash. This value was collected by slaughtering the pig, just like how you might break a piggy bank to access the coins it stores.

This down-to-earth connection between pigs and thrift helps explain why the animal became a symbol of savings in many cultures. In Germanic folklore, pigs represent luck and plenty. Someone who’s had a stroke of good fortune is said to have Schwein gehabt — literally, “got pig.” Even today, New Year’s Eve in parts of Europe is celebrated with marzipan or chocolate candies known as “lucky pigs.” It was likely German immigrants, with their own Sparschwein (“saving pig”), who carried this fond association to the United States around the start of the 20th century.