The Rise and Fall of the ‘Farmers’ Almanac’

For more than two centuries, the Farmers’ Almanac was a familiar presence in American homes — tucked beside seed catalogs, wedged between cookbooks, pinned on barn walls, or kept in workshop drawers. Its pages offered long-range weather predictions, planting calendars, sunrise and moon-phase charts, home remedies, and practical advice. For generations, it influenced how people prepared for the seasons and understood the cycles of the natural world.

The Farmers’ Almanac regularly included weather lore, folk sayings, planting guidelines, and proverbs — a blend of traditions that resonated with a mostly rural, agrarian readership. Many of the proverbs are sayings Americans still recognize today, such as “A stitch in time saves nine.” Others have much older European or colonial origins, and the almanac played a role in keeping them alive and circulating.

But the long tradition of the Farmers’ Almanac will end with the publication’s 2026 edition. The publishers announced the closure in late 2025, citing rising costs, dwindling print readership, and the reality that digital tools now offer immediate forecasts and guidance once found only in annual books. As the Farmers’ Almanac closes its doors, let’s take a look at the rise and fall of this former household staple.

A Tradition Older Than America

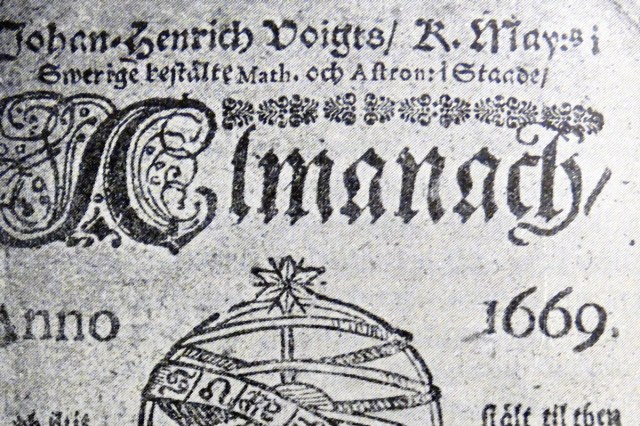

Almanacs are far older than the United States. Their roots go back to ancient societies that tracked celestial events to guide planting and seasonal work. With the invention of the printing press, the earliest known printed almanacs emerged in Europe — the first appeared in 1457 — and by the late 15th century, such publications commonly included calendars, astronomical data, tide tables, and practical seasonal guidance.

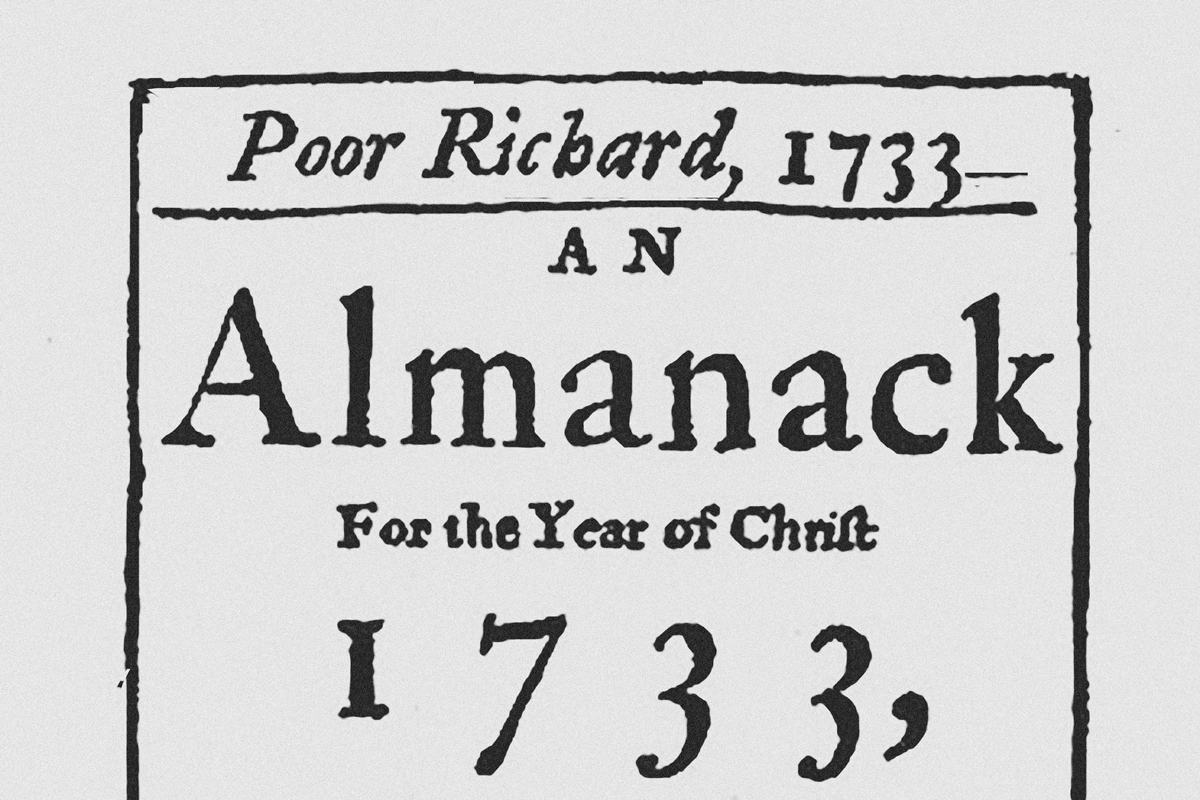

In colonial North America, the tradition of almanac‑making began in the 17th century. The first U.S. almanac was printed by William Pierce in 1639, offering calendars, weather guidance, and seasonal advice for the New England region. By the 18th century, dozens of almanacs circulated across the colonies. Perhaps the most famous was Poor Richard’s Almanack, first published by Benjamin Franklin in 1732.

Despite the many almanacs that sprang up, only a handful endured into the modern era. At the center of that legacy are two long‑running American institutions: The Old Farmer’s Almanac and the Farmers’ Almanac, which carried forward the tradition of annual almanacs centuries after their 15th‑century predecessors across the pond.