The Most Bizarre Elections in U.S. History

The first line of the preamble to the U.S. Constitution contains the oft-referenced statement of purpose, “to form a more perfect union.” Presidential elections have served as a significant (if not the most significant) part of the process behind that intention, as a quadrennial evaluation of the not-yet-perfect union’s direction. As with any growth process though, there’s bound to be some, well, awkward phases — and the United States certainly has had them. Entire political parties have come and gone, constitutional amendments have been necessitated, and there’s been all manner of outright oddity throughout the history of U.S. presidential elections. Here are some of the most bizarre moments.

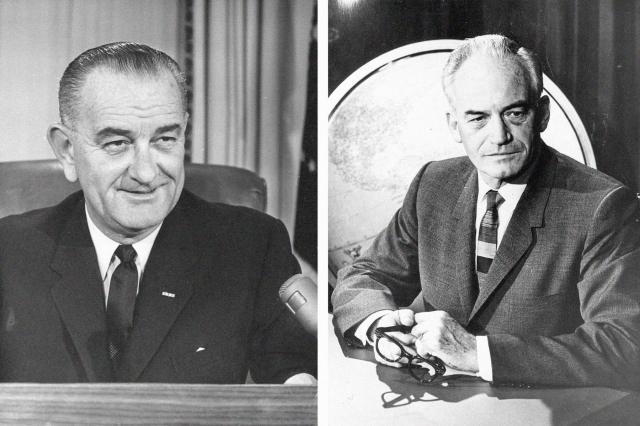

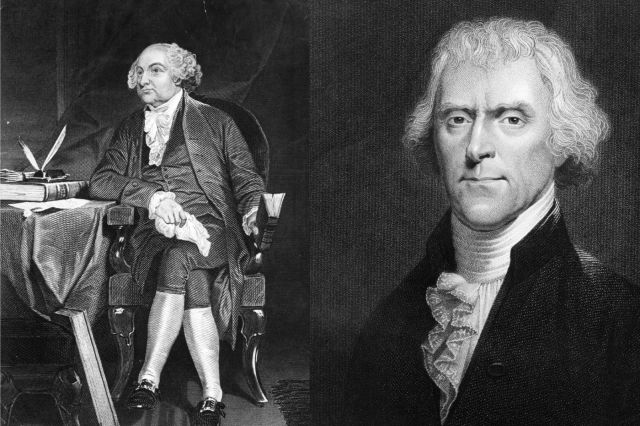

1800: John Adams vs. Thomas Jefferson

If anything proves that partisan politics and electoral machinations are nearly as old as the United States itself, it’s the election of 1800, when Federalist Party incumbent President John Adams sought reelection against Democrat-Republican Vice President Thomas Jefferson. The already-bizarre premise of opposing parties holding the presidency and vice presidency was made possible at the time by a law stipulating that the presidential candidate who earned the second-most number of electoral votes became Vice President. In the election of 1796, Jefferson lost the presidency to Adams by only three votes, and the 1800 election was a rematch between the political rivals.

That time, with another narrow margin likely, both parties turned toward influencing electors, whose votes decided the winning candidate in states where there was not yet a popular vote. Jefferson wrote of his intent to sway electors in New York, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey in a letter to James Madison. Federalist Senator Charles Carroll accused Jefferson and his supporters of also attempting to use “arts and lies” to manipulate votes in Federalist-leaning Maryland. From there, the accusations, well, escalated. Jefferson-supporting pamphleteer James Callendar claimed that John Adams was a hermaphrodite. Federalist newspapers accused Jefferson of maintaining a harem at Monticello.

When the votes were finally cast, the election ended in a tie between Jefferson and… his intended running mate, Aaron Burr. How? Each elector had two votes to cast, but there was no distinction at the time between a vote for President versus a vote for Vice President. Casting one vote for Jefferson and one vote for Burr was in effect a vote for each as President. The Constitution called for resolving this tie between the Democrat-Republican candidates with a vote in the House of Representatives, which was controlled by, you guessed it, the Federalist Party.

The task at hand was to vote on who, between Jefferson and Burr, would be President, but the Federalists saw an opportunity to seize power, either by delaying the proceedings past the end of Adams’ term, or attempting to invalidate enough votes to give Adams the majority. Others advocated for supporting Burr. Between February 11 and February 16, 35 rounds of voting took place, each ending in deadlock. Finally, after much lobbying by Alexander Hamilton against Burr, the 36th ballot resulted in Jefferson being appointed President. In the wake of the turbulent election, the 12th Amendment was ratified in order to prevent a repeat ordeal in 1804.

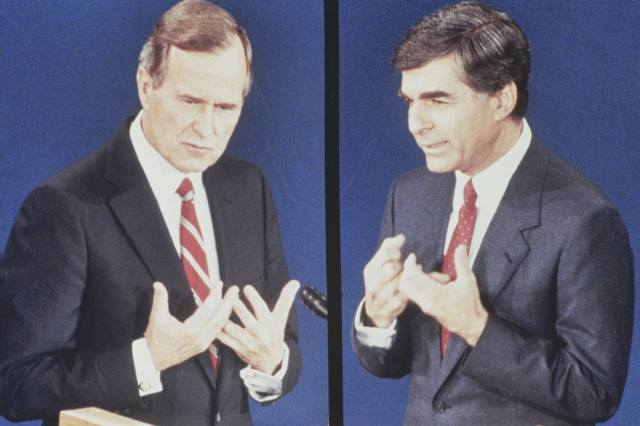

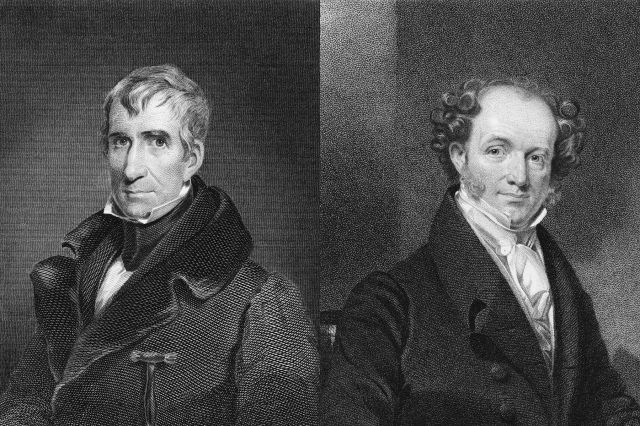

1840: William Henry Harrison vs. Martin Van Buren

If William Henry Harrison is known today, it’s for the obscurity of his mere 31 days in office. But the campaign leading to his presidency was a rollicking and often rowdy phenomenon that sparked a voter turnout of more than 80%, an increase of nearly 23 percentage points from the previous election.

The election pitted Harrison and running mate John Tyler of the upstart Whig Party against incumbent Democratic President Martin Van Buren during a period of economic strife caused by the Panic of 1837. Harrison’s campaign played off of his military fame for his victory at the Battle of Tippecanoe, with the slogan “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too.” It also attacked Van Buren with accusations of living in aristocratic luxury. The Van Buren campaign and its supporters countered by painting the 67-year-old Harrison as too elderly and frail for the presidency. An editorial in the Baltimore Republican mocked Harrison with the line, “Give him a barrel of hard cider, and settle a pension on him… he will sit the remainder of his days in his log cabin by the side of the fire and study moral philosophy!”

The Whigs, however, embraced the hard cider and log cabin imagery, and built the rest of the campaign around it. They leaned into the association with the “everyman,” and organized cider- and whiskey-fueled mass rallies. There were songs, stump speeches, and all manner of bric-à-brac emblazoned with cider kegs and log cabins. There were also the 10- to 12-foot slogan-covered balls Whigs would roll down the streets while chanting in support of the candidates. It all led to Harrison shellacking Van Buren in the election, albeit not quite as might be expected: The lopsided victory was in the Electoral College, 234 to 60, but the popular vote margin was only about 150,000 votes. No need to pity Van Buren, though. He later remarked, “The two happiest days of my life were those of my entrance upon the office and my surrender of it.”