How Was Mail Delivered Before House Numbers?

Though mail is almost an afterthought today with the amount of correspondence conducted online, we can still count on bills, holiday cards, and various other goodies to arrive with the mail carrier’s visit.

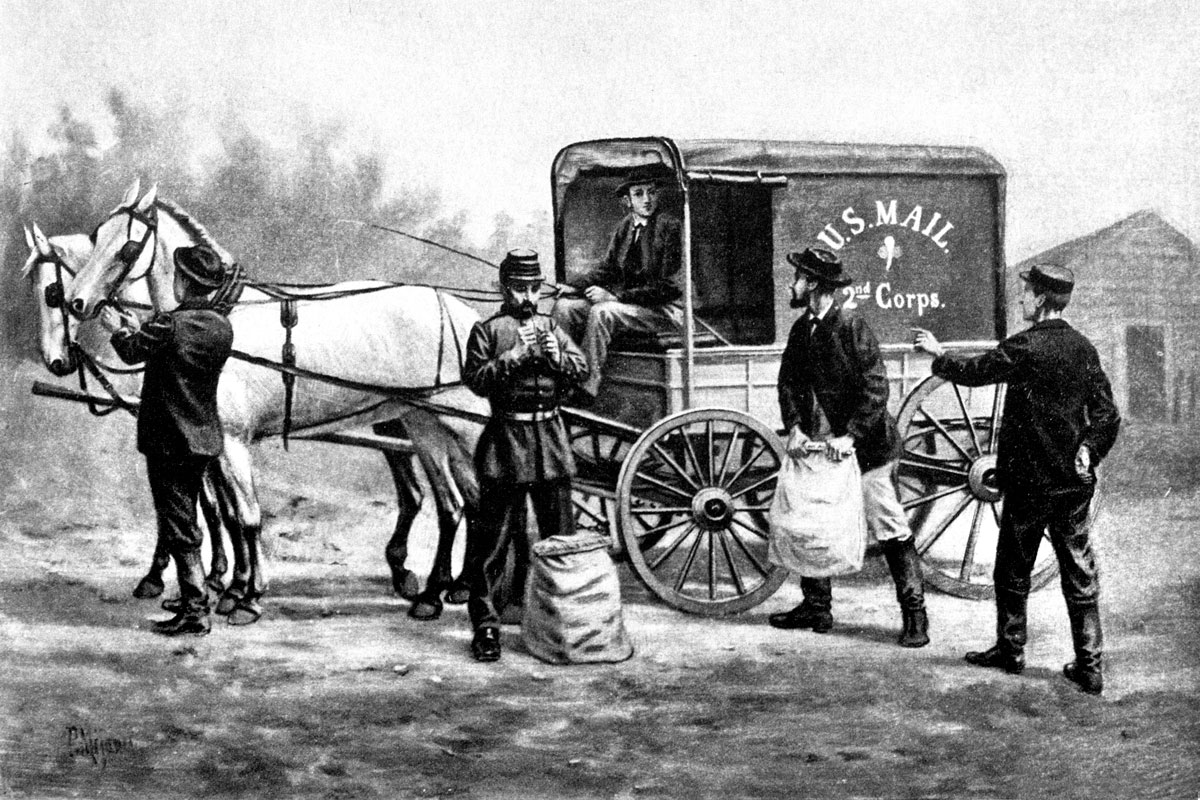

The daily post enabled the exchange of information before radio, television, or the internet — and it wasn’t always an easy feat. Mail trucks and planes do the heavy lifting now, but delivery once depended on the pace of trains and steamboats, and before that the physical capabilities of equestrian and human carriers.

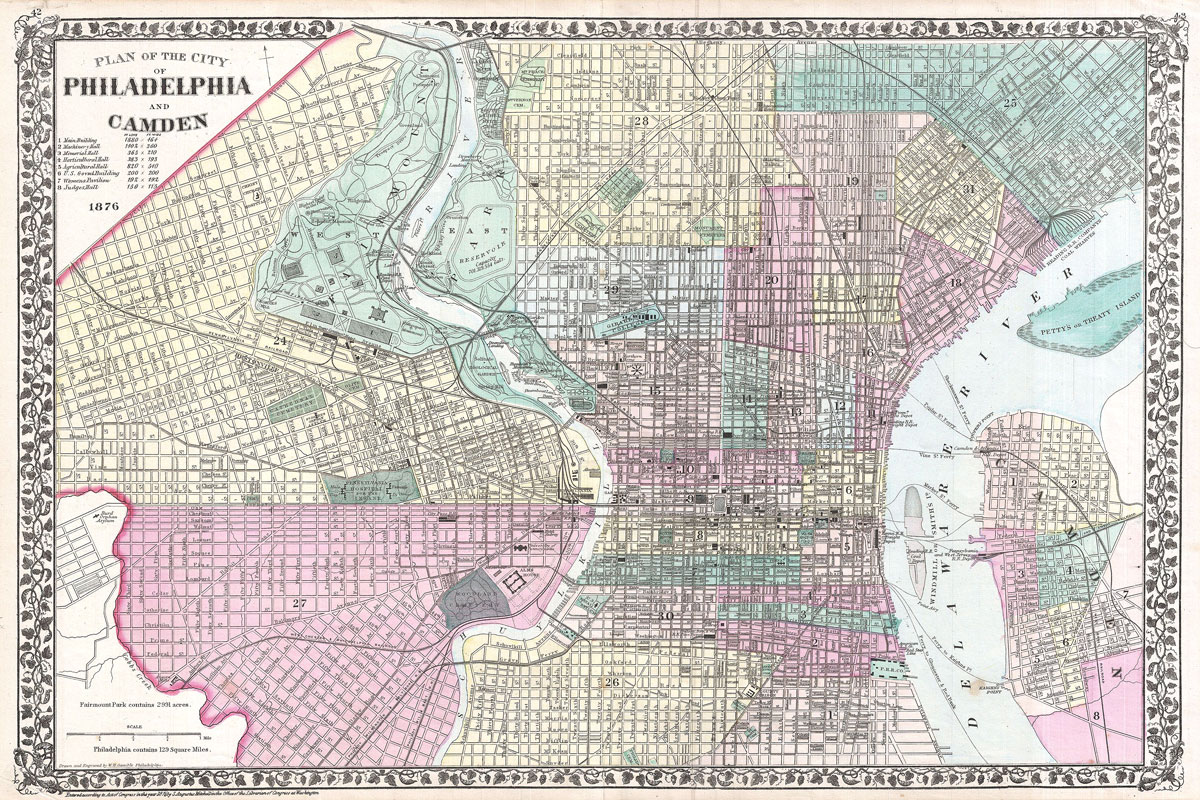

Another complicating factor was the lack of an established street address system for a good chunk of U.S. history. Given all these complications, one could be forgiven for wondering just how mail ended up in the right hands without an exorbitant number of mistakes in the olden days. Here’s a look at how the Post Office Department, the precursor to the United States Postal Service (USPS), found its way.

Early Mail Service Required a Trip to the Post Office

The first post office in the American colonies was established in a Massachusetts tavern in 1639, with the first intercolonial systems surfacing in the 1670s. In this era of sparse settlements, mail delivery was often handled by enslaved people or Native American carriers who knew the terrain well.

By 1789, when a Congressional Act under the brand-new U.S. Constitution placed the postmaster general under the power of the executive branch, there were 75 post offices and some 2,400 miles of post roads spread along the Eastern Seaboard. While this ensured mail access for most Americans, people needed to travel to the nearest post office to retrieve it.

There were exceptions to this rule. Benjamin Franklin, who became deputy postmaster of the colonies in 1753 and later the first postmaster general of the United States, established the “penny post” home delivery service in Philadelphia for a fee.

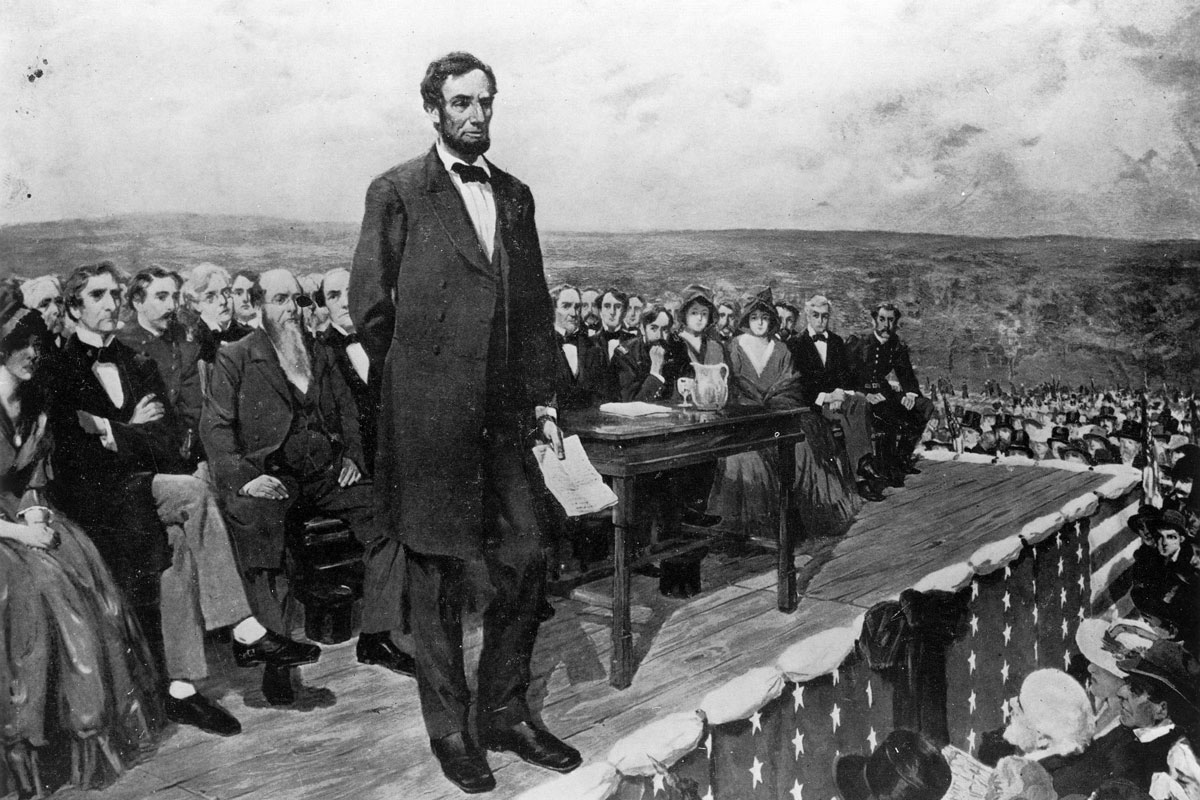

Several of the private mail companies that materialized in the 1800s also would deliver mail to a recipient’s door, while a postmaster in a smaller town, such as a pre-presidential Abraham Lincoln, might find time to stop by the homes of those unable to retrieve their mail. By and large, however, home delivery service was not a reality for most Americans before the Civil War.