6 Rich Facts About the Gilded Age

The Gilded Age didn’t last long — just a few decades from the 1870s to around 1900 — but it left an outsized impact on American history. This was the age of Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller; of massive fortunes built on steel, oil, and railroads; and of families such as the Astors and Vanderbilts showing off their wealth in palatial “summer cottages” by the sea.

Beneath the glitter and gold, however, the era was marked by deep inequality, brutal child labor, and sharp racial divides. While the upper class flaunted luxury, most Americans faced grueling work, poverty, and discrimination — and these realities shaped the nation as much as the gilded façade.

The clash of glamour and grit, extravagance and unrest, keeps the stories of the Gilded Age surprisingly fresh today. Here are six fascinating facts about the era that you might not know.

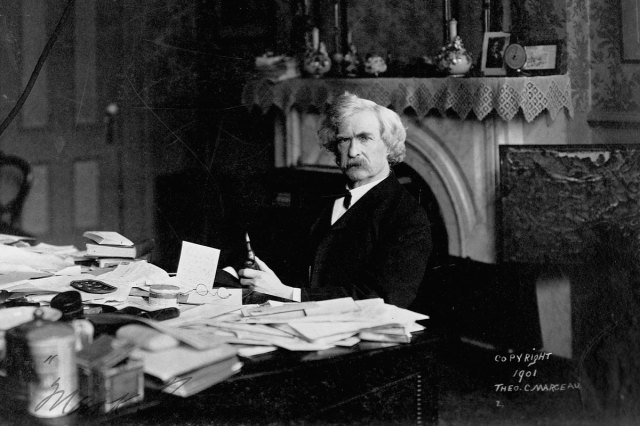

Mark Twain Gave the Gilded Age Its Name

The phrase “Gilded Age” came from satirists, not historians. In 1873, Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner published The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today, a novel lampooning political corruption, land speculation, and society’s obsession with wealth. The word “gilded” describes a thin layer of gold over something far less valuable — so the phrase was a critique of the greed and superficiality in the decades after the U.S. Civil War.

At the time, wealthy elites didn’t use the term. Many saw themselves as a kind of American aristocracy, where vast fortunes signified refinement, progress, and even natural superiority. By the 1920s and ’30s, however, historians and social critics embraced Twain’s label, expanding it to describe the era from the 1870s through the turn of the 20th century, capturing both its dazzling wealth and the deep social inequities beneath the surface.

“Dollar Princesses” Helped Rescue Britain’s Nobility

As American fortunes rose, many British aristocratic families were cash-poor but land-rich. Enter the “dollar princesses”: American heiresses whose wealth revitalized English estates with an influx of much-needed funds. Consuelo Vanderbilt’s 1895 marriage to the Duke of Marlborough brought in $1.6 million (around $60 million today) to restore Blenheim Palace, while Jennie Jerome’s $250,000 dowry (more than $9 million today) helped pave the way to her 1874 marriage to Lord Randolph Churchill (Winston Churchill’s father). These enormous dowries helped to maintain estates, pay staff, and fund the lifestyle of the nobility.

By some estimates, more than 450 American heiresses married into European nobility, making wealth a decisive factor in transatlantic unions. In fact, there were so many marriages between “dollar princesses” and the British aristocracy that at one point they accounted for roughly a third of the titles in the House of Lords.