5 Facts About the World’s Oldest Countries

While some modern countries are little more than a decade old, others boast a rich history dating back thousands of years. Long before nations such as Iran and Egypt became the independent states we know them as today, early governments were formed by ancient civilizations in those regions, laying the foundation for thousands of years of expansion and development.

It can be a challenge to determine the exact age of any given country, but based on the current archaeological data, there are several nations in the Middle East and Asia that consistently rank among the oldest in human history. Here are five facts about some of the world’s oldest countries.

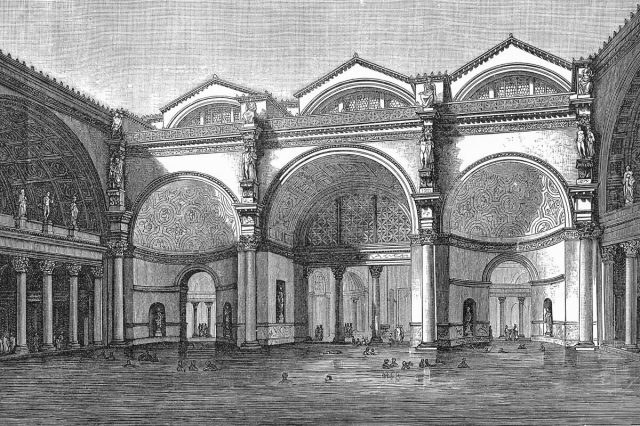

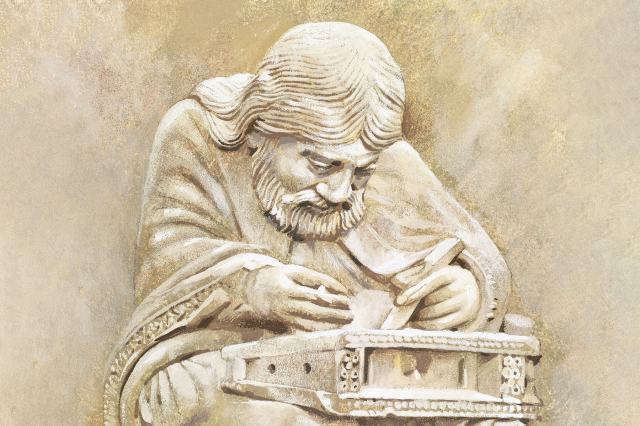

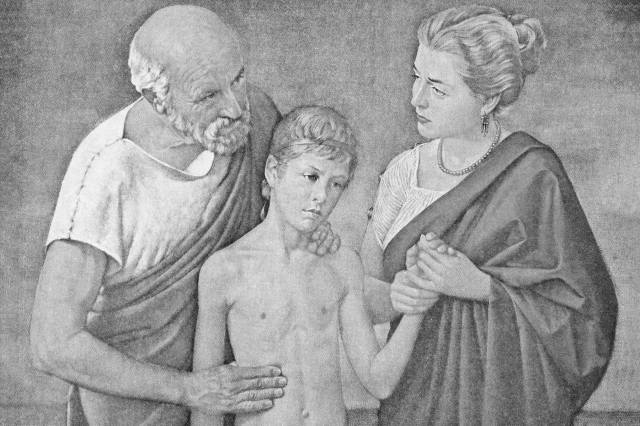

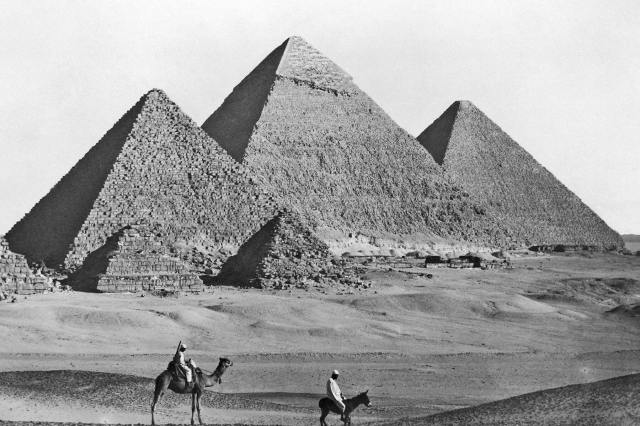

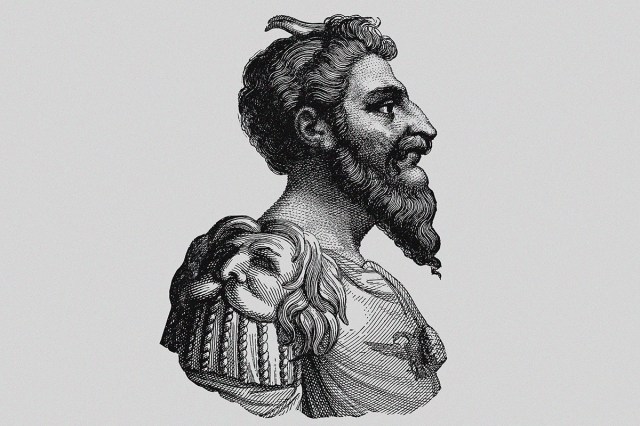

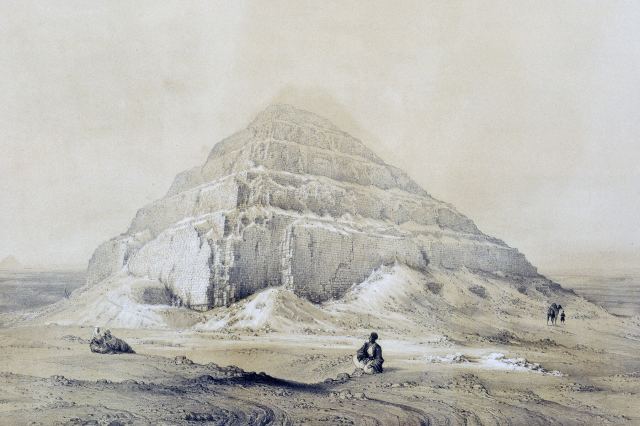

The First Architect Known by Name Lived in Ancient Egypt

Though the Great Pyramids of Giza are the most famous ancient Egyptian landmarks, the region is home to an even older structure. The Pyramid of Djoser — built in the mid-27th century BCE — predates the Great Pyramids by roughly a century, and was designed by a man named Imhotep, who is considered to be one of human civilization’s first architects. Imhotep not only conceived of this groundbreaking pyramidal structure, but also gets credit for using columns before anyone else and revolutionizing the use of stone in building construction. He also offered vast contributions to the world of medicine, writing texts describing the early diagnosis and treatment of many ailments. In 525 BCE, centuries after his death, Imhotep even rose to the status of full deity, being dubbed the Egyptian god of science, medicine, and architecture.

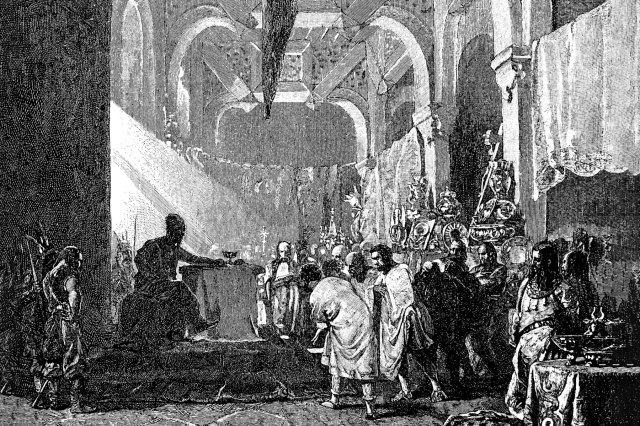

Two Vietnamese Sisters Led a Successful Revolt Against China

According to Vietnamese legend, the origins of Vietnam date back to around the year 2879 BCE, which marked the beginning of the Hồng Bàng dynasty — the first recorded dynasty in the nation’s history. For millennia, the Vietnamese people ruled over their own territory, which was invaded by members of China’s Han dynasty in 111 BCE. After a century of Chinese control, two women rose up to push back against their Chinese invaders, earning the status of national heroes in the process. The Trưng sisters — Trưng Trắc and Trưng Nhị — mobilized locals in an effort to avenge the death of the former’s husband, who had been executed by Chinese forces without trial. This newly formed army consisted of around 80,000 soldiers and 36 female generals. The forces rebelled against the Chinese in the year 39 CE, successfully driving the invaders out of the country. Though the sisters’ reign over the region was brief, as China recaptured the territory in 43 CE, the legend of their exploits and tragic fate only grew from there. Temples were dedicated in their honor throughout Vietnam, as people prayed to them for rain in times of drought. They remain important figures in Vietnamese history two millennia later.