The Rise and Fall of Sears Mail-Order Homes

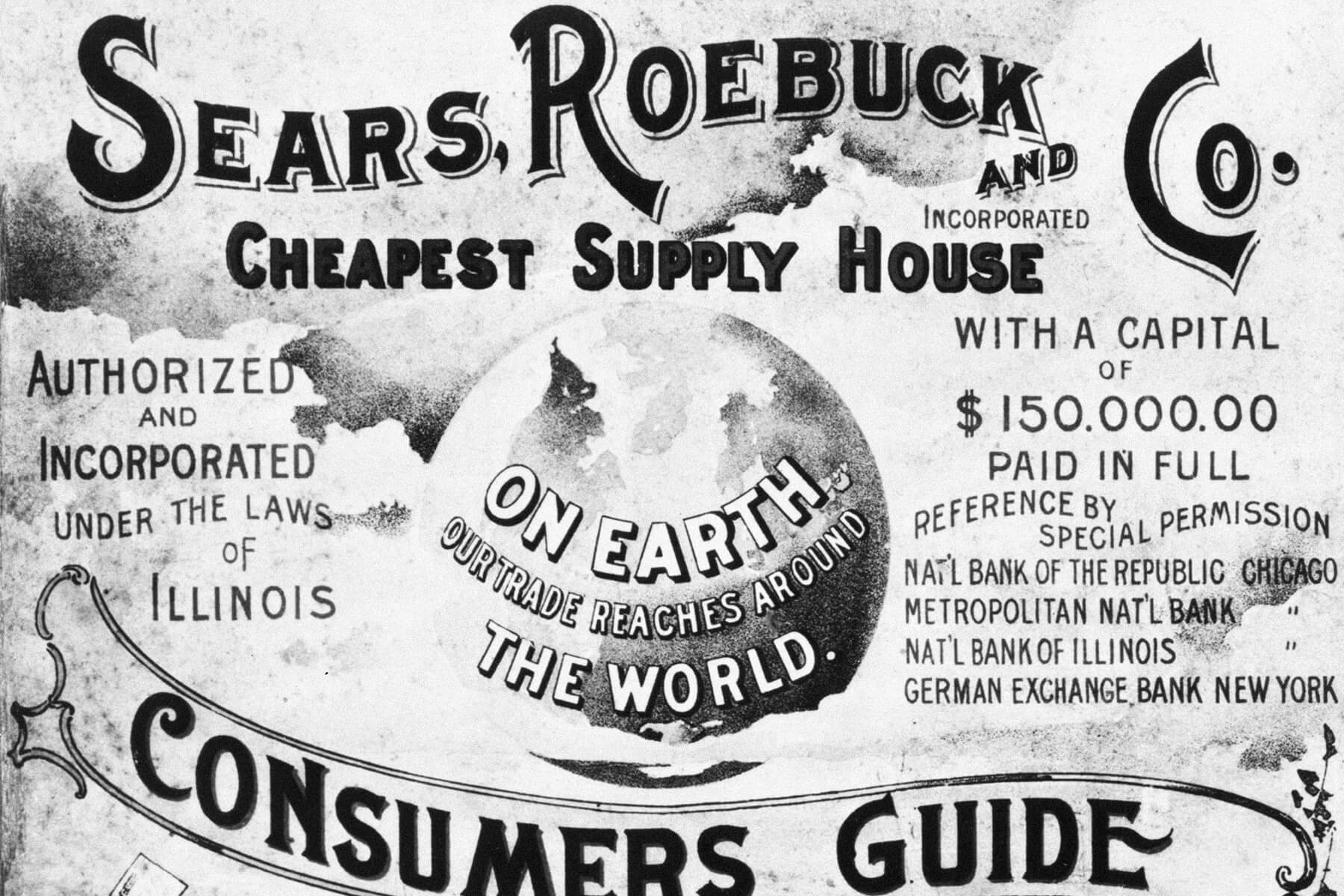

In 1906, Sears was a flourishing catalog company that had just launched a highly successful initial public offering. The company went public under the name Sears, Roebuck and Co. after completing the construction of an enormous new headquarters and distribution center in Chicago, which totaled 3 million square feet of floor space over 40 acres of land. Sears advertised the new complex as “the largest mercantile plant in the world,” and included illustrations of it on the backs of its catalogs. It was a heady time for the company, but not everything was running smoothly.

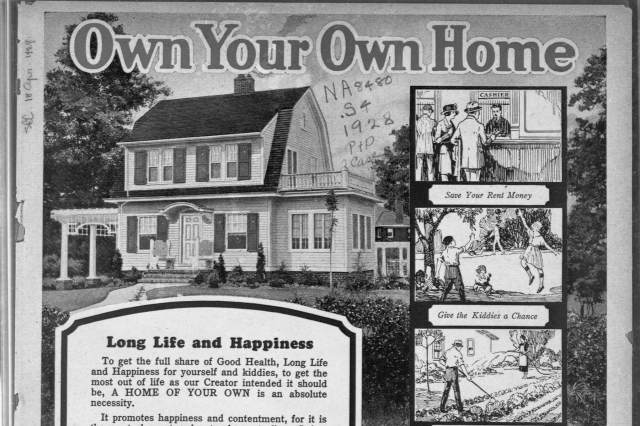

Though Sears was growing, its building supplies department was proving unprofitable, and a decision to close it loomed. Manager Frank W. Kushel was appointed to oversee the liquidation of the department, but he instead developed a way to sustain it: All the supplies needed to construct a home were bundled together with blueprints, and shipped directly from the factory. This eliminated the need to warehouse the materials, thus saving costs, while simultaneously creating a bigger-ticket product line. The Book of Modern Homes and Building Plans — the first catalog of Sears mail-order houses — was sent to prospective customers in 1908.

Sears was not the first company to sell kit houses — the Aladdin Company, Montgomery Ward, Lewis Homes, and others were also in the market around the same time — but Sears touted its status as one of the “largest commercial institutions in the world” with its massive distribution center, and promised to save customers between “$500 and $1,000 or more” in building costs, while guaranteeing the quality and reliability of materials. Balloon-style framing design, with drywall instead of lath and plaster, reduced the carpenter hours needed to build a house, in turn lowering the total cost for the buyer. In the initial 1908 catalog, 22 home designs were offered, ranging in price from $650 to $2,500 (roughly $20,000 to $80,000 today) and in sizes from unassuming to approaching grandeur.

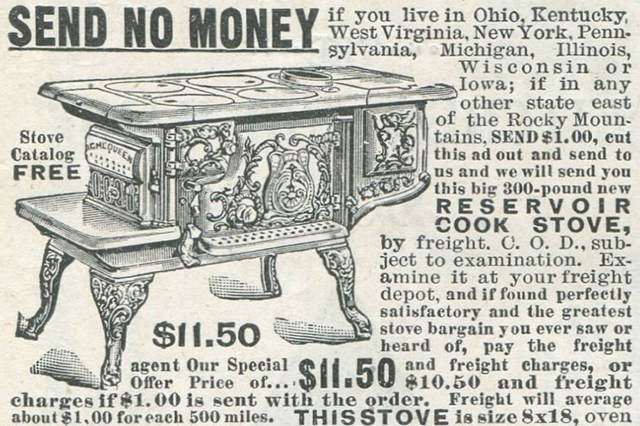

Not surprisingly, delivery of materials was a complex operation. The average buyer didn’t have the space to store all the building pieces at once, so shipments were phased. The lumber and nails for the frame arrived first, in order to allow the roof and enclosure to be built, thus ensuring adequate shelter for the ensuing materials. When the customer was ready, they sent for the next shipment, which included millwork and inside finish. Hardware, paint, and any additional furnishings were the third and final shipment.

The majority of mail-order houses arrived by train; the buyers hauled the materials from the boxcar to their building site, unless they were well heeled enough to pay for the railroad to truck the supplies from the station. The first orders for homes were placed by customers around late 1908 or early 1909.

Sears moved aggressively to improve home offerings and stimulate sales. In 1909, it acquired a lumber mill in Mansfield, Louisiana. The following year, electric lights and gas (high-end amenities at the time) were included in home designs. The next two years saw the completion of an additional lumber mill in Cairo, Illinois, and the acquisition of a millwork plant in Norwood, Ohio.

The new facilities enabled the company to manufacture its entire line of homes using its own sources, which allowed for an expanded number of home designs. By 1912, the Modern Homes department reached an annual sales volume of $2,595,000, which equated to a profit of $176,000. This was enough to wipe out the previous losses from the department’s former building supplies incarnation. Kushel’s plan was a success.