What’s the Real Story of Ben Franklin’s Kite Experiment?

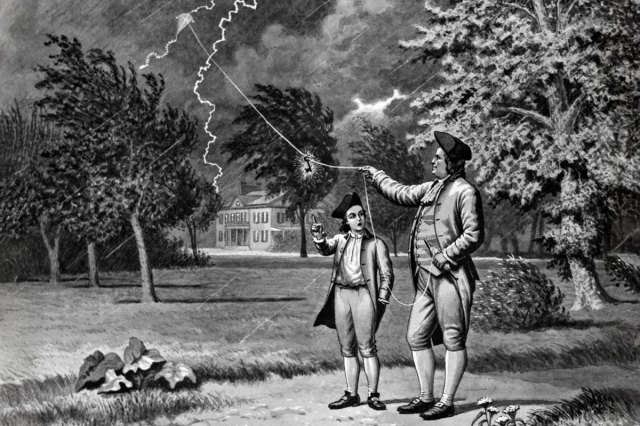

It’s one of the most well-known moments in American history: Ben Franklin attaching a key to a kite during a thunderstorm to demonstrate the electrical nature of lightning. Yet, like a centuries-long game of telephone, the details of the celebrated 1752 experiment have been exaggerated or misinterpreted through countless retellings, creating a popular myth that may be more fiction than fact.

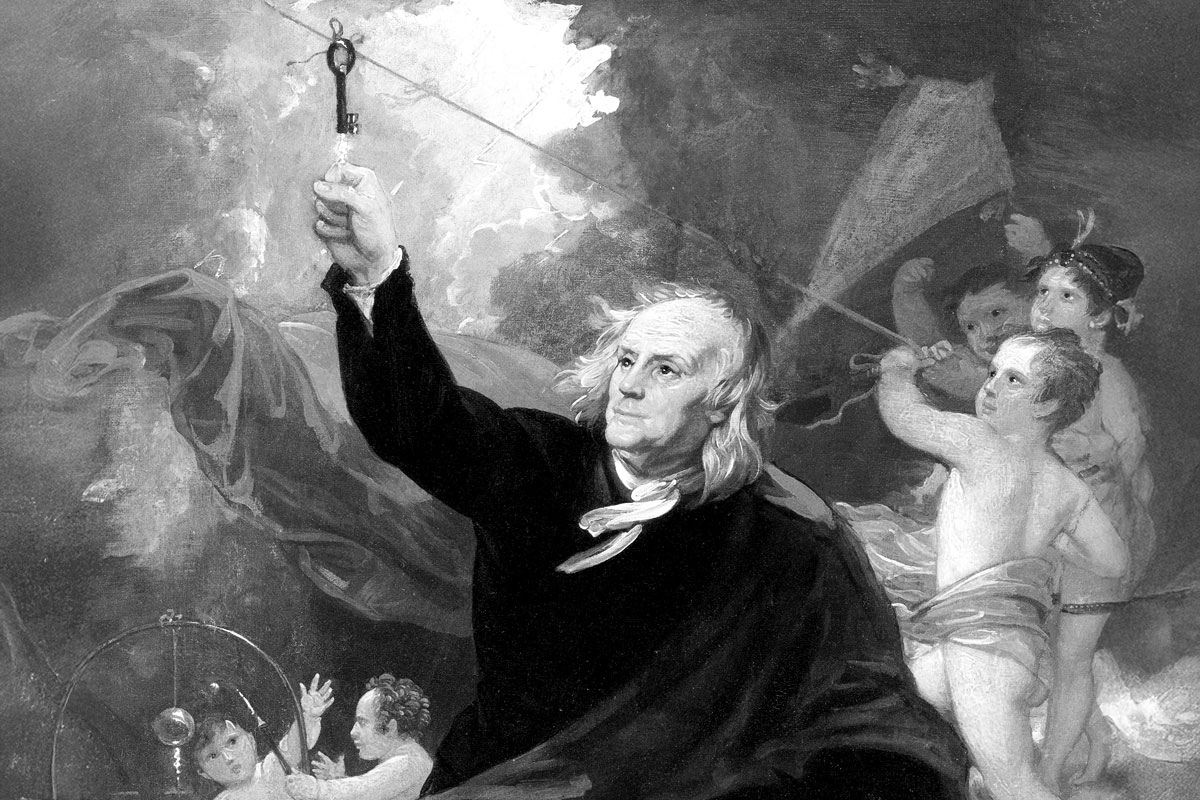

Look no further than the oil-on-canvas work “Benjamin Franklin Drawing Electricity From the Sky,” painted by Benjamin West in the early 19th century. In the painting, a confident Franklin raises his fist to receive a charge from a key suspended by a kite string, hair and cape billowing around him, as a team of cherubs wrestles with the string and another pair engage with some sort of electrical apparatus in the background.

This work of art encapsulates much of the myth surrounding the famous experiment. The dramatic portrayal clearly isn’t meant to be taken as a historically accurate re-creation, and West took several liberties with his depiction of the event. For one thing, Franklin was actually assisted in this endeavor by his young adult son William, not a team of cherubs. The inventor was also a relatively spry 46 at the time, not yet the wizened elder seen in the painting. And he likely undertook his experiment from the shelter of a shed, as opposed to being exposed to the elements of a thunderstorm.

What’s more, the kite and key story, retold to countless schoolchildren over the past two centuries and often repackaged as Franklin’s “discovery” of electricity, may not have taken place at all. While that’s certainly a more extreme interpretation of what happened, it also underscores the scarcity of verified details about the most famous experiment from one of the most famous figures in American history. So what really happened?

Franklin’s Theories on Electricity

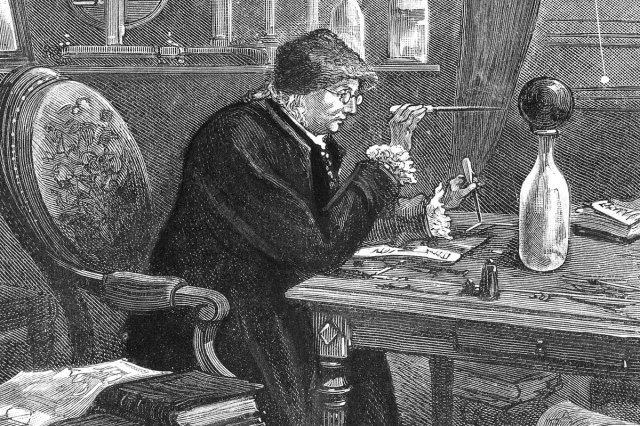

As told in Walter Isaacson’s Benjamin Franklin: An American Life, the titular polymath, then best known as a Philadelphia printer, turned his considerable intellectual gifts toward exploring the little-understood properties of electricity in the 1740s. Conducting an array of experiments with a Leyden jar, a simple capacitor fitted with a cork and wire, Franklin formed what became the single-fluid theory of electricity with his observation of a flow between “positive” and “negative” bodies with an excess or absence of the fluid.

Franklin also became intrigued by the similarities between electrical sparks and lightning, and devised ways in which to demonstrate their shared nature. In a 1749 collection of notes, later relayed in a 1750 letter to Franklin’s London business partner Peter Collinson, Franklin described how such a demonstration could be administered: “On the top of some high tower or steeple, place a kind of sentry-box, big enough to contain a man and an electrical stand. From the middle of the stand, let an iron rod rise and pass bending out of the door, and then upright 20 or 30 feet, pointed very sharp at the end. If the electrical stand be kept clean and dry, a man standing on it when such clouds are passing low, might be electrified and afford sparks, the rod drawing fire to him from a cloud.”

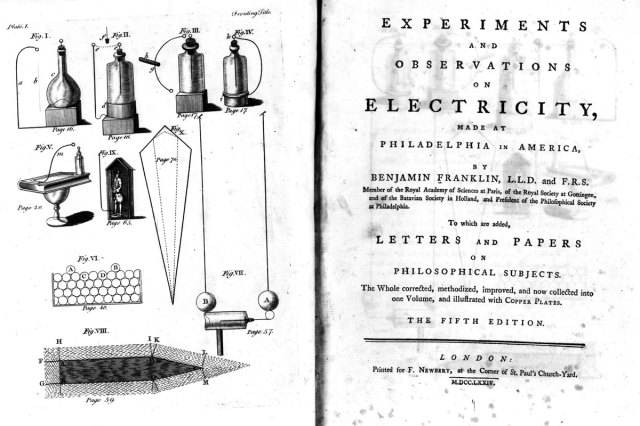

The European scientific community began seriously considering Franklin’s work around this time, particularly after a series of his letters and notes were published in the 1751 pamphlet Experiments and Observations on Electricity. In May 1752, French naturalist Thomas-François Dalibard followed Franklin’s proposed instructions for drawing sparks from a storm cloud, his success inspiring colleagues to produce their own demonstrations that proved the American’s theory that lightning is a form of electrical energy.