During the French Revolution, most of the country did not speak French.

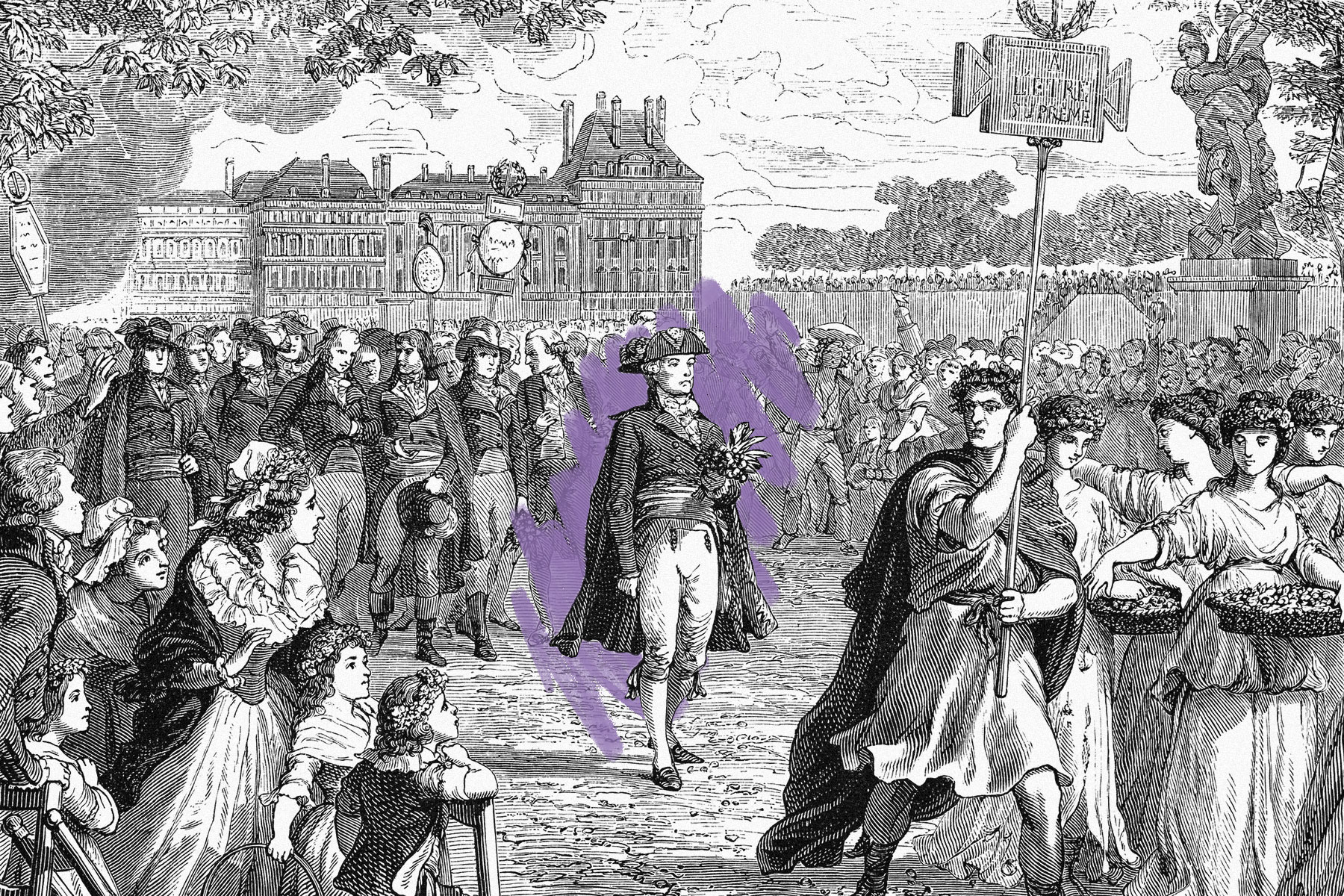

In the early years of the French Revolution, a revolutionary named Henri Grégoire conducted a survey of language throughout the fledgling republic and discovered a concerning truth: Most people living in France at the time didn’t actually speak French. On June 4, 1794, Grégoire reported the results of his survey to the revolutionary assembly, stating that there were no more than 3 million French speakers (11% of the population), and even fewer who were able to write it. In fact, the language was spoken more in the Netherlands and German states than it was in some parts of France.

Instead, a majority of French people spoke local dialects — for instance, a large southern population spoke Occitan, a Romance language influenced by Latin. This was seen as particularly embarrassing for the revolutionary cause, as three years earlier, diplomat Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand declared that “the multitude of corrupt dialects, the last remnants of feudalism, will be forced to disappear: necessity dictates so.” Grégoire’s survey only added fuel to the fire. Little more than a month after the survey, the revolutionary administration declared that “no public act may be written (or registered) other than in the French language, in any part of the territory of the Republic.” Luckily, France’s linguistic multiculturalism survived the prescriptive onslaught, and regional languages such as Occitan and Basque flourish to this day.