What Was George Washington’s Inauguration Like?

Every four years, a new United States presidential administration commences with an inauguration ceremony on the western front of the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C. Held on January 20, or January 21 if the traditional date falls on a Sunday, the inauguration begins around noon with the vice president-elect reciting the oath of office.

That’s followed by the only constitutionally mandated component of the inauguration, the president’s oath of office, typically administered by the chief justice of the United States. The president-elect repeats the words: “I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will faithfully execute the office of president of the United States, and will to the best of my ability, preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States.”

The president then delivers their inaugural address, followed by a luncheon in the Capitol’s Statuary Hall, and a parade that takes the chief executive and their party to the White House. The evening’s events include varying numbers of official and unofficial balls, held in hotels and government buildings throughout the city.

While the roots of these traditions go back to the very first U.S. presidential inauguration — that of George Washington in 1789 — the events of that particular day were noticeably different from what transpires now. In fact, the ceremonies surrounding this landmark moment of American history weren’t even formalized until just a few days before it all unfolded.

A Military Procession Escorted George Washington to New York City

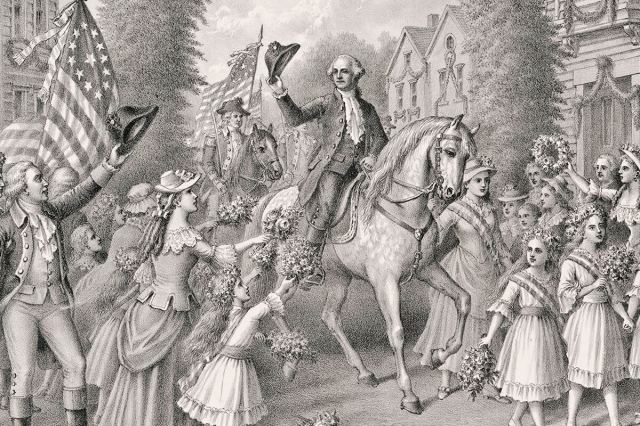

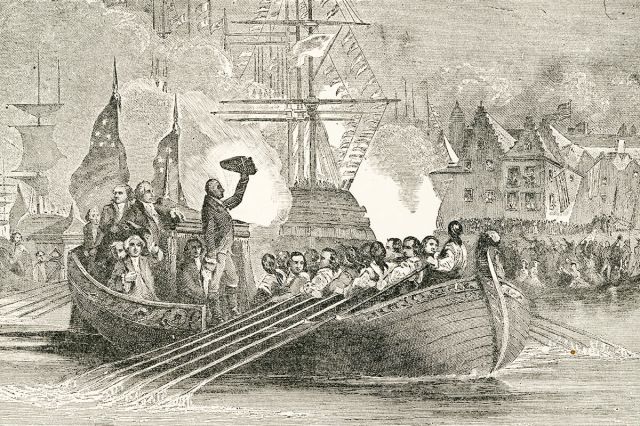

Following a week’s journey from his beloved Virginia plantation Mount Vernon, which saw him feted by residents of every town he passed through, Washington arrived at his new home in what was then the federal capital, New York City, on April 23, 1789. His wife, Martha Washington, who was still tending to business at Mount Vernon, did not join him for another month.

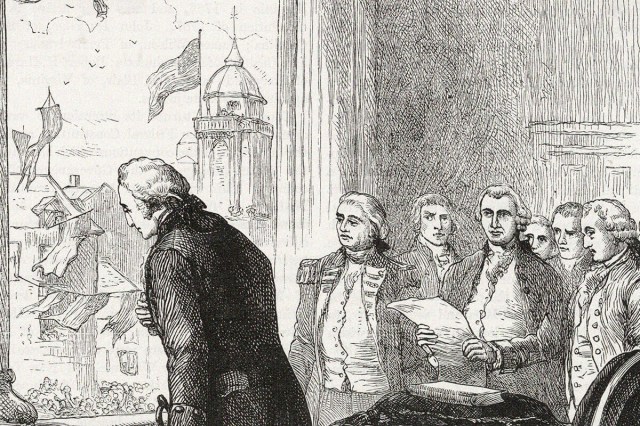

With the president’s safety secured, a joint committee of the Senate and House of Representatives met to hammer out details of where the inauguration would take place, who would administer the oath of office, and seating arrangements. On April 25, Congress adopted the committee’s recommendations for ceremonies to be held five days later.

At sunrise on the determined day of April 30, a military salute was discharged at Fort George near the southern tip of Manhattan. At 9 a.m., church bells sounded throughout the city for approximately half an hour, summoning their congregants for a morning service.

Meanwhile, Washington, who’d had barely any downtime since adjusting to his accommodations in a three-story brick building on Cherry Street, dressed in a Connecticut-made brown broadcloth suit, adorned with gilt buttons engraved with the arms of the United States, as he awaited the military procession that would escort him to Federal Hall on Wall Street.

The escorts arrived around noon and set off with the president in his coach about half an hour later. Numbering some 500 men in total, the procession included two companies of grenadiers, a company of light infantry, members of the Senate and House committees, and the Spanish and French ministers.

Within 200 yards of Federal Hall, the procession split into lines on either side of the street, its participants presenting arms and lowering flags as Washington and his party passed between them on foot and entered the federal building.

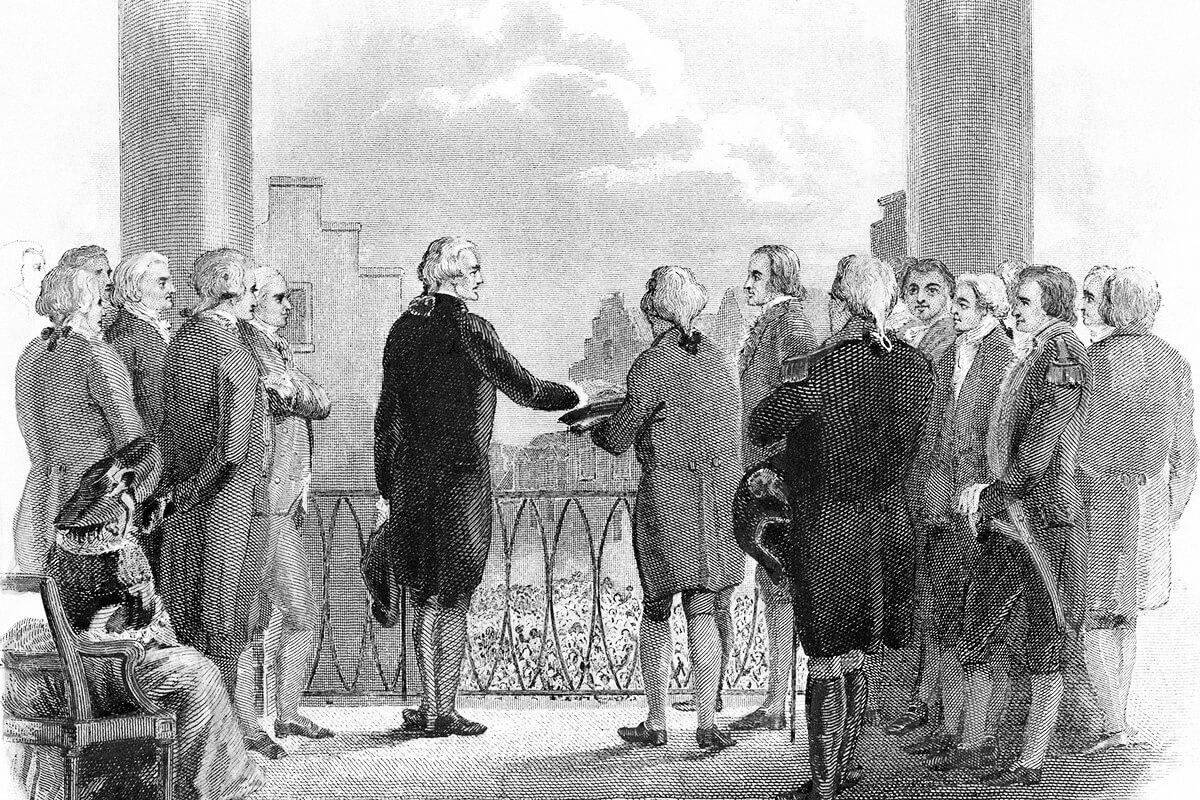

Inside the Senate Chamber, Washington was greeted by his vice president, John Adams, and members of both the Senate and House of Representatives. At about 2 p.m., Adams informed Washington that it was time to take the oath of office, and the gathered congressmen escorted the president to a canopy-covered balcony decorated with red and white curtains.

Before a crowd of spectators gathered on the streets below, and on the roofs and balconies of neighboring buildings, Washington placed his right hand on an open Bible supplied by St. John’s Masonic Lodge of New York and repeated the oath of office administered by the chancellor of New York, Robert R. Livingston. After the president finished by kissing the Bible, Chancellor Livingston turned to the crowd and ignited a celebratory roar by proclaiming, “It is done; long live George Washington, president of the United States.”