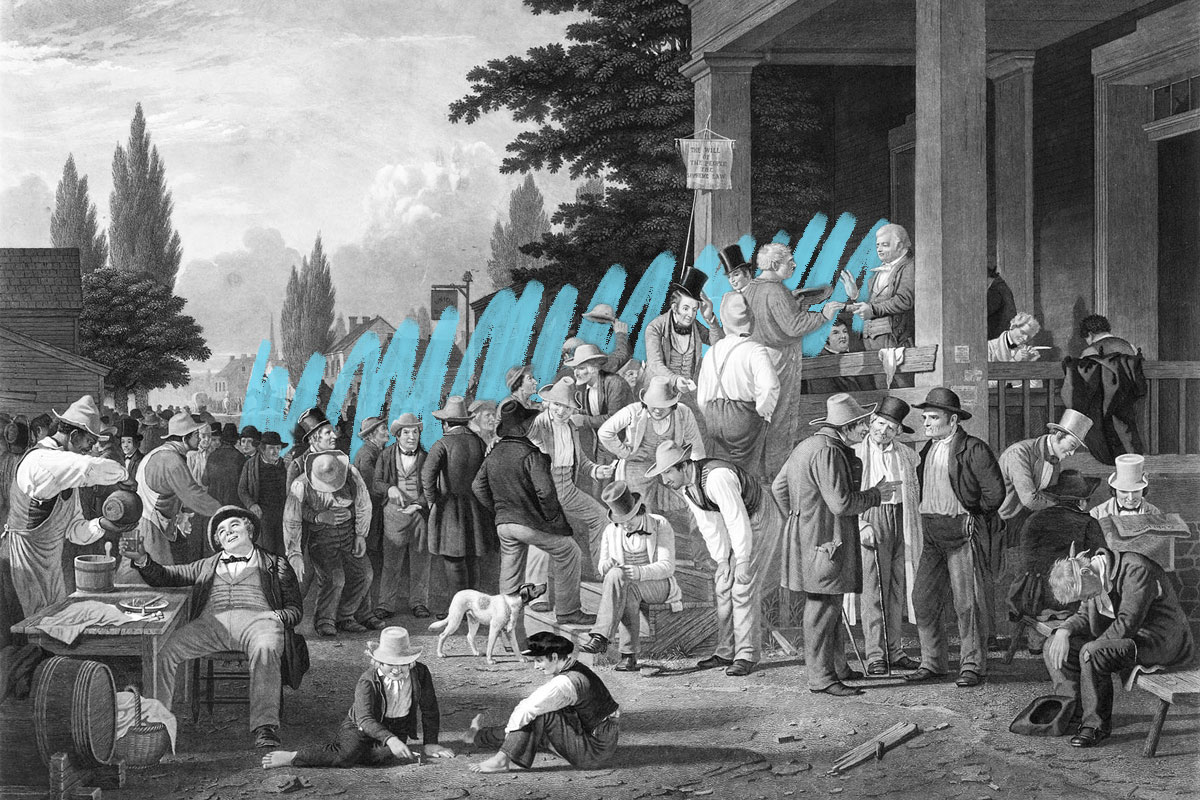

People used to vote by voice in colonial America.

Just because colonial Americans were subject to taxation without representation doesn’t mean they never voted. Indeed, elections were often held to select local officials and members of colonial legislatures. Rather than paper ballots, however, colonists voted by voice in a practice known as “viva voce.” This being the past and all, voting machines were centuries away from being invented, and paper ballots, despite having been around since ancient times, had yet to be widely adopted in the American colonies. So voters would gather in a public venue and announce their choice out loud for all to hear.

Like most of the country’s early political traditions, viva voce came to America’s shores from the other side of the pond. It was the norm not only in Britain but also in the Netherlands, German provinces, and Scandinavia, eventually becoming law in six American colonies before also being adopted in Arkansas, Illinois, Kentucky, Missouri, Oregon, and Texas.

The public nature of viva voce was considered a feature rather than a bug because, as English philosopher and politician John Stuart Mill put it, “The voter is under an absolute moral obligation to consider the interest of the public, not his private advantage.” Old habits die hard, and viva voce persisted until the end of the 19th century. Fears that it was conducive to voter intimidation led to the current private ballot system, though not quickly. Five of the 33 U.S. states at the time still used viva voce in the 1850s, and nearly 10% of the votes in the 1860 presidential election won by Abraham Lincoln were cast by voice. The last holdout was Kentucky, which phased out the practice in 1891.