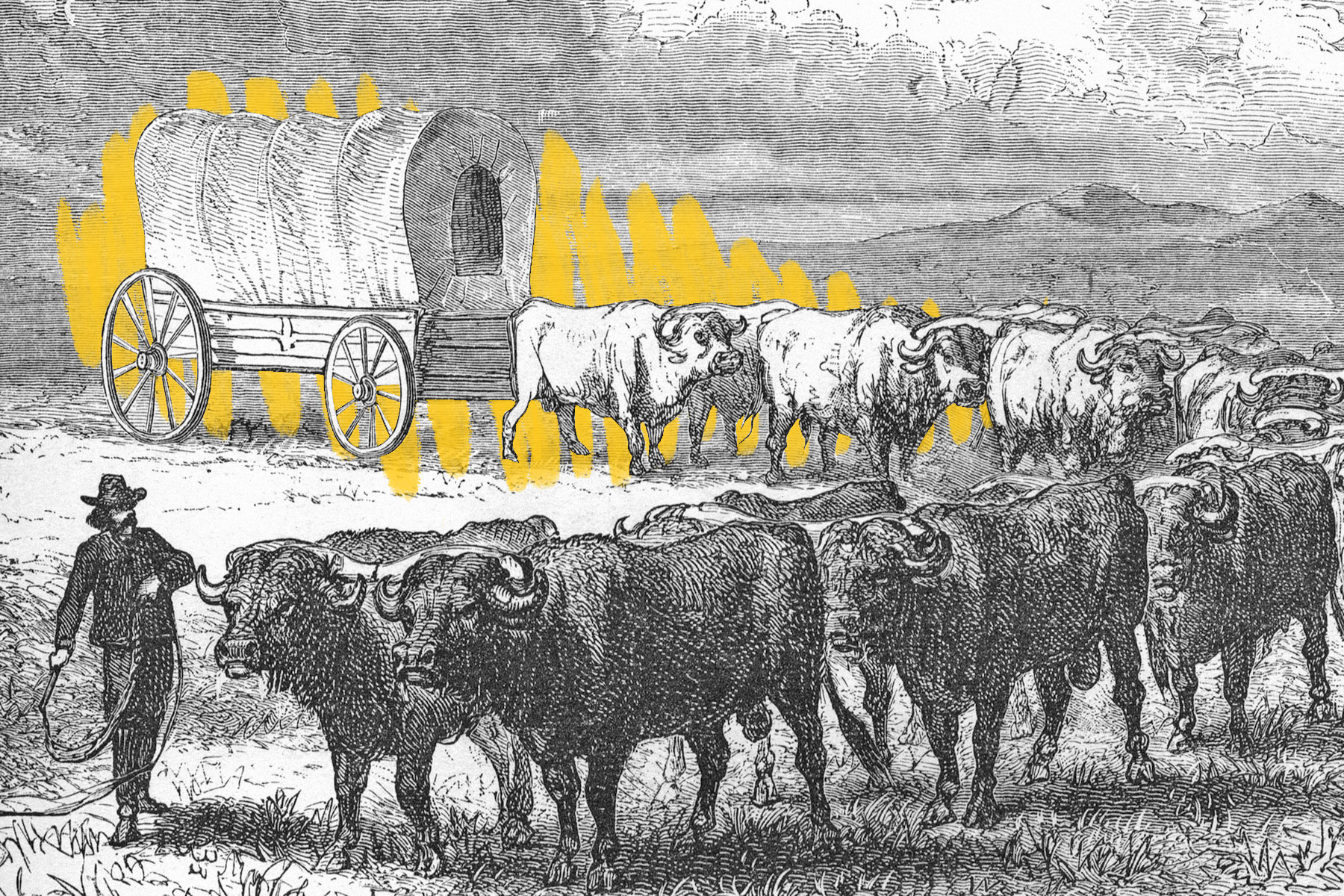

The Oregon Trail wagons weren’t for passengers.

It’s often thought that the Oregon Trail was made easier by the covered wagons that have become synonymous with the grueling journey, but that’s only partially true. Those wagons weren’t actually for people, who walked most or all of the trail’s 2,000 miles from Independence, Missouri, to Oregon City, Oregon. Instead, they were for the supplies that hopeful settlers deemed necessary for the trek, pulled by mules and oxen. Indeed, people who were ferried by wagons had a habit of falling out, as the vehicles didn’t have springs and thus bounced around a lot; some folks were even run over by other wagons or trampled by beasts of burden after falling. As for those walking, many of the children didn’t have shoes.

So while we often romanticize that months-long journey as being emblematic of the “American Dream” and westward expansion, it was above all else a brutal quest that many did not survive. Contrary to popular belief, however, that has little to do with Indigenous peoples. Tribes such as the Pawnee and Shoshone were more likely to be trail guides or trading partners than hostile combatants, and fatigue and disease caused the vast majority of settlers’ deaths. When they circled the wagons at night, it wasn’t to keep Indigenous peoples out — it was to keep animals in.