How the Postal Service Created the ZIP Code

Even with the decline of letter writing in the digital age, the ZIP code remains an American institution, a neat five-digit number that caps an address and, like an area code, can serve as a point of pride and prestige.

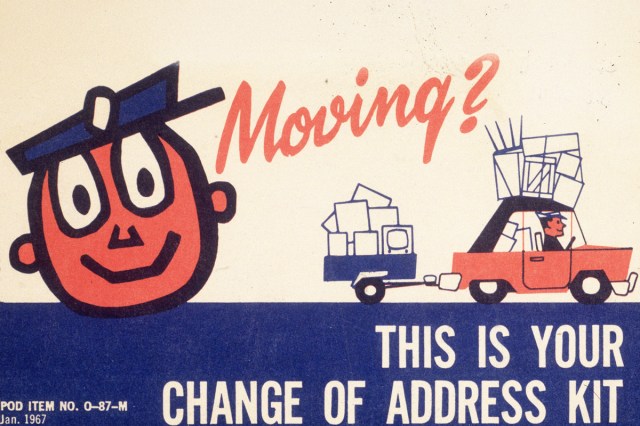

Given the ZIP code’s place as an oft-used and universally recognized symbol, it may come as a surprise that the ZIP, short for “Zone Improvement Plan,” isn’t all that old. The system was enacted on July 1, 1963, within many of our lifetimes and just a few months before another famous entity, the Beatles, also arrived in the United States.

But unlike the mop-topped quartet, the five-digit zoning plan wasn’t immediately welcomed by Americans. Here’s a look at how the ZIP code came to be, and ultimately overcame a bumpy start to emerge as a signature accomplishment of the United States Postal Service.

An Early Zoning System Came Out of World War II

Like many innovations, the ZIP code’s origins can be traced back to World War II. At the time, the Post Office Department, as the U.S. Postal Service was then called, was dealing with the loss of personnel to military duty, specifically the departure of experienced sorters who could properly funnel letters and parcels marked with incomplete addresses.

As a result, in 1943, the department assigned one- to two-digit zone numbers to more than 100 high-density urban areas across the country to help make sorting for these areas more efficient. The numbers were to be written on the address of the recipient after the city name, such as “Indianapolis 24, Indiana.”

Although the zone numbers provided some organizational relief, they only papered over the problem of keeping up with the ever-growing volume of mail. Fueled by the country’s postwar population and economic boom, the number of individual pieces of mail jumped from 33 billion in 1943 to 66.5 billion in 1962. By the latter date, a letter was handled by an average of eight to 10 postal employees, increasing the possibility of human error.

The issue wasn’t going unnoticed by the department’s employees. In 1944, a prescient postal instructor named Robert Moon sought to get ahead of the volume problem with his proposal of splitting the country into a network of regional processing centers, each marked by a three-digit code. Nine years later, another inspector, H. Bentley Hahn, completed a six-year study of the department’s outdated operations with a report titled “Proposed Reorganization of the Field Postal Service.”

But despite the modernization efforts of Postmaster General Arthur Summerfield, who introduced the country’s first automated post office in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1960, the department was still struggling to meaningfully address its problems as it faced down a new decade.