A volcanic eruption indirectly led to the invention of the bicycle.

The bicycle may seem like a symbol of leisure or health today, but its roots lie in disaster. In 1815, Mount Tambora in Indonesia erupted with extraordinary force, blasting ash, gas, dust, and rock high into the atmosphere. (It’s now considered the largest volcanic eruption in recorded history.) The fallout dimmed the sun worldwide, lowering temperatures and devastating harvests. The following year became known as the “year without a summer” — snow fell in July in New England, crops withered in Europe, and famine spread.

The shortages were catastrophic for both people and animals. In Germany, where food prices soared, horses were slaughtered for meat or starved for lack of feed, primarily oats. This sudden scarcity of horsepower — the main mode of transport at the time — spurred a new line of thinking. If animals couldn’t be relied on for transportation, perhaps people could move themselves.

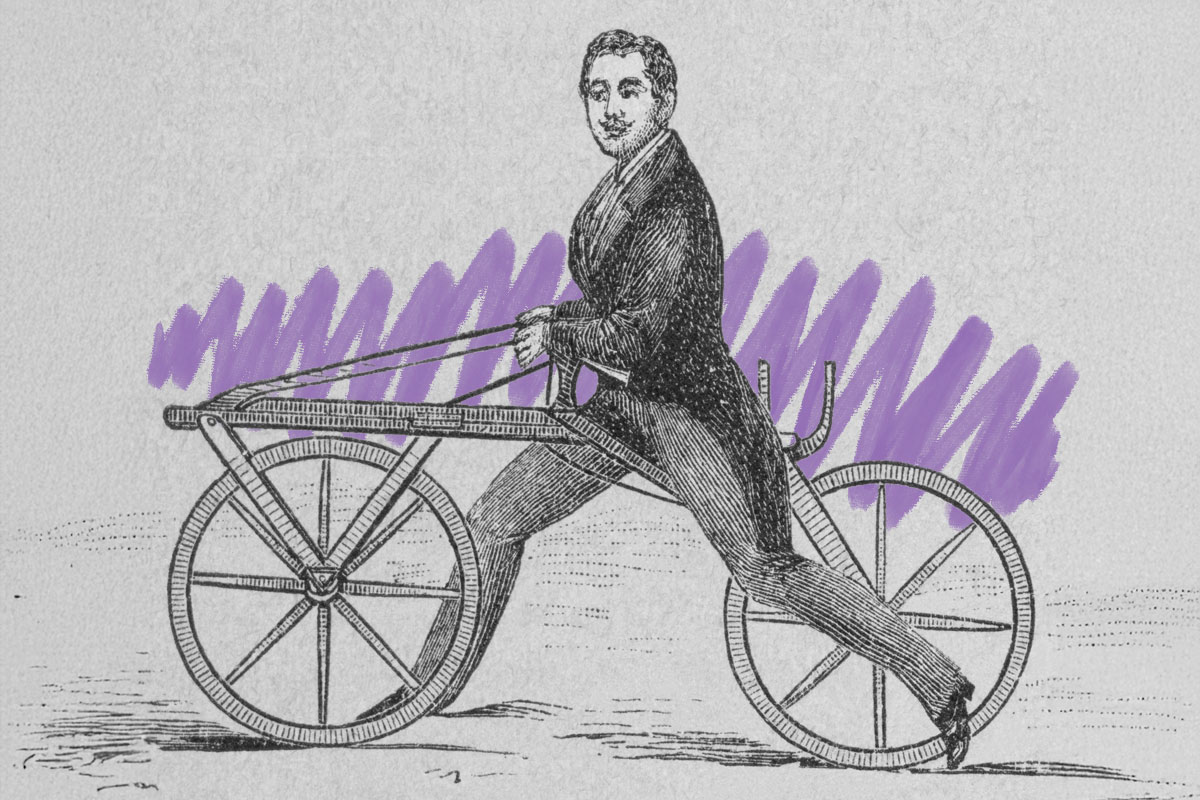

Enter Baron Karl von Drais, a German civil servant and amateur inventor. In 1817, he unveiled his Laufmaschine, or “running machine” — a simple two-wheeled wooden frame that riders straddled and propelled by pushing their feet along the ground. It could travel far faster than walking, even on muddy post-rain roads. Drais demonstrated it with a 50-kilometer ride (about 31 miles) over four hours that proved its practicality. Though it was mocked as a “dandy horse” and was even restricted in some cities, Drais’ design (also known as a “draisine”) encouraged the idea of human-powered transport. Over the decades, innovators added pedals, gears, and chains, transforming his running machine into the modern bicycle.