Women wrote nearly all early Japanese literature.

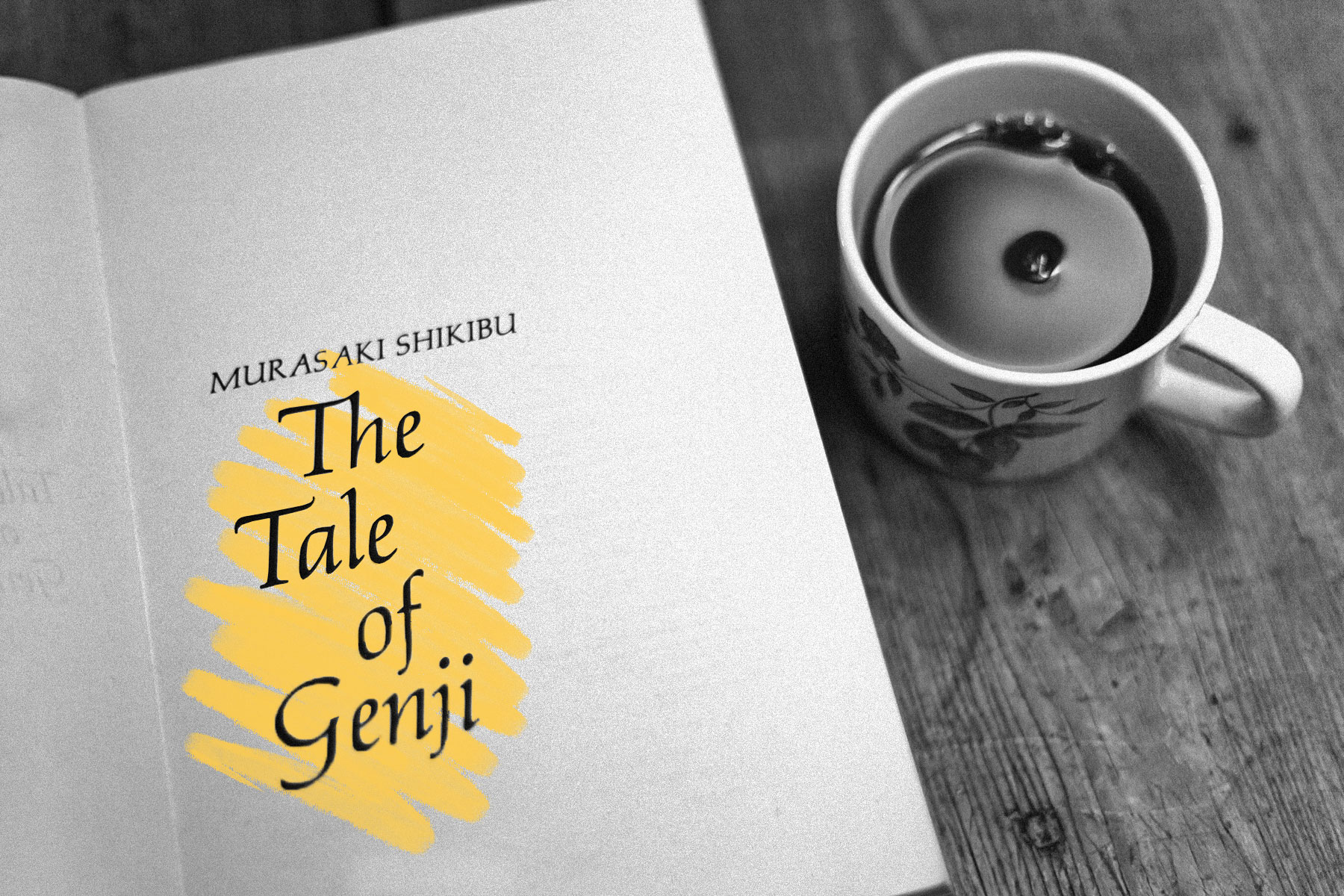

There’s a good chance you already knew that The Tale of Genji was the world’s first novel, but it’s less likely that you knew it was written by a woman. Murasaki Shikibu, a lady-in-waiting at the imperial Japanese court, was the author in question, and she began a trend that lasted for centuries: women penning nearly all early literature that was written in the Japanese language. Aristocratic men eschewed their native tongue in favor of Chinese during the Heian period (794–1185), leaving women who were denied a formal education to rely on Japanese for personal and creative expression. The hiragana script, one of the language’s three syllabaries, was even referred to as onna-de, or “women’s hand.”

Shikibu wasn’t the only woman of her era to have a massive influence on Japanese literature. Of nearly equal importance were Sei Shōnagon, who wrote a book of observations on imperial court life called The Pillow Book, and the poet Izumi Shikibu. Considered by many to have been the foremost poet of her era, she’s especially well remembered for love poems such as “If the One I’ve Waited For”: “If the one I’ve waited for / came now, what should I do? / This morning’s garden filled with snow / is far too lovely / for footsteps to mar.” As the Heian period ended and the Kamakura period began, women found themselves in a lower position under the feudalistic government and had fewer opportunities to write. The literature of this era, which was written almost entirely by men, reflects the many wars that Japan experienced.