Why Do We Have Middle Names?

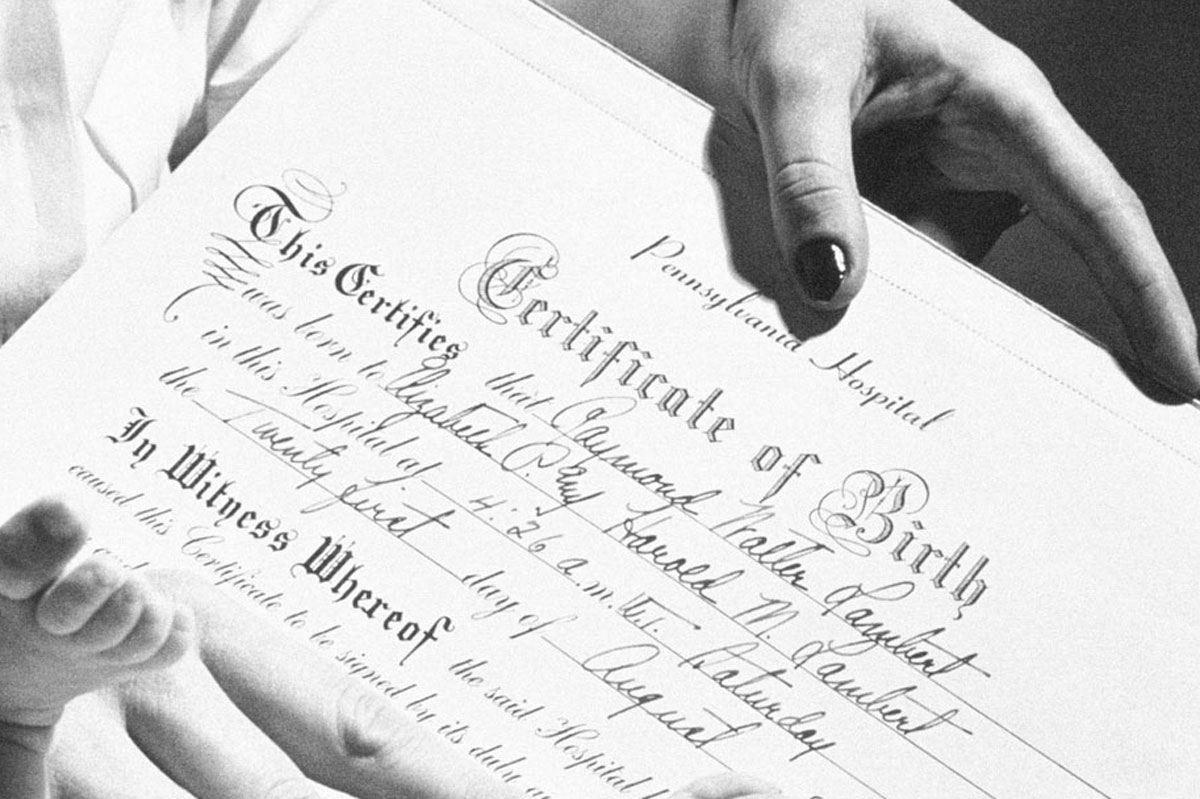

Middle names are a strange concept. They often lie silent and unused, only to emerge when we fill out official forms and documents, providing an extra piece of proof as to who we are, despite our near-total disregard for the name in our daily lives. In the U.S., a majority of people have a middle name, but only around 4% of people are referred to by it. And, according to a poll by The Atlantic, only about 22% of Americans think they know the middle names of at least half of their friends or acquaintances.

A valid question therefore arises: Why do we have middle names? What’s the point, and who got us started with this seemingly superfluous naming process? Here, we take a look back through history to see when and why middle names emerged, and how they became commonplace.

The Emergence of Middle Names

Though historians don’t know exactly when middle names originated, we do know the ancient Romans used a naming system that, at times, involved what can be considered a middle name. Some Romans, especially members of the aristocracy, used a three-part naming system called tria nomina, consisting of a praenomen (personal name), nomen (family name), and cognomen (additional identifier). But the nomen, while having the same placement as a middle name, had a different function — as a family identifier, similar to modern surnames — so it’s not a clear precursor to the middle names we use today.

Instead, we have to fast-forward to medieval Europe. According to historian Stephen Wilson in The Means of Naming: A Social History, the custom of giving middle names emerged (or possibly reemerged) in Italy around the late 13th century. The naming practice became common among the Italian elite, who saw the middle name as extra real estate for honoring saints, family members, or political allies — offering a perceived spiritual or social boost.

The trend caught on, and by the Renaissance era it was increasingly common for wealthy families across Europe to include middle names during baptisms. From there, it filtered down through the social classes to become commonplace among rich and poor alike. In France, for example, more than half of all boys were given just a first name during the first decade of the 19th century. In the last decade of that century, less than a third had only a first name, while 46% had one middle name and 23% had two. By that time, middle names were common in Europe and had also traveled to the United States, helping cement their position as a standard part of Western naming practices.