5 Major Firsts in TV History

For all the formulaic sitcoms and talk shows that have run throughout the history of television, there are a number of times when audiences have witnessed true ingenuity. From memorable commercials to shocking plot twists, television events that may seem commonplace today once revolutionized the medium. Ever since the demonstration of the first television in 1926, the small screen has been a reflection of larger shifts in American society. With that in mind, here are five historic firsts in television history.

The First Official TV Commercial

On July 1, 1941, at 2:29 p.m., viewers tuning in to the NBC-owned WNBT television station saw something they had never seen before. Before that day’s broadcast of the Brooklyn Dodgers vs. Philadelphia Phillies baseball game, the first authorized TV commercial hit the airwaves. The inaugural ad was produced by Bulova watches and ran for about 60 seconds, featuring visuals of a clock superimposed over a map of the United States with the accompanying voice-over, “America runs on Bulova time.”

The watchmaker paid just $9 to broadcast the advertisement ($4 for air fees and $5 for station fees), a far cry from the exorbitant advertising prices of today. WNBT was also the only station to advertise that day, though other networks soon followed suit. The Federal Communications Commission had previously implemented an advertising ban that forbade television commercials, though broadcasters still ran ads without authorization. The FCC finally issued 10 commercial licenses on May 2, 1941 — ushering in a new chapter in television history.

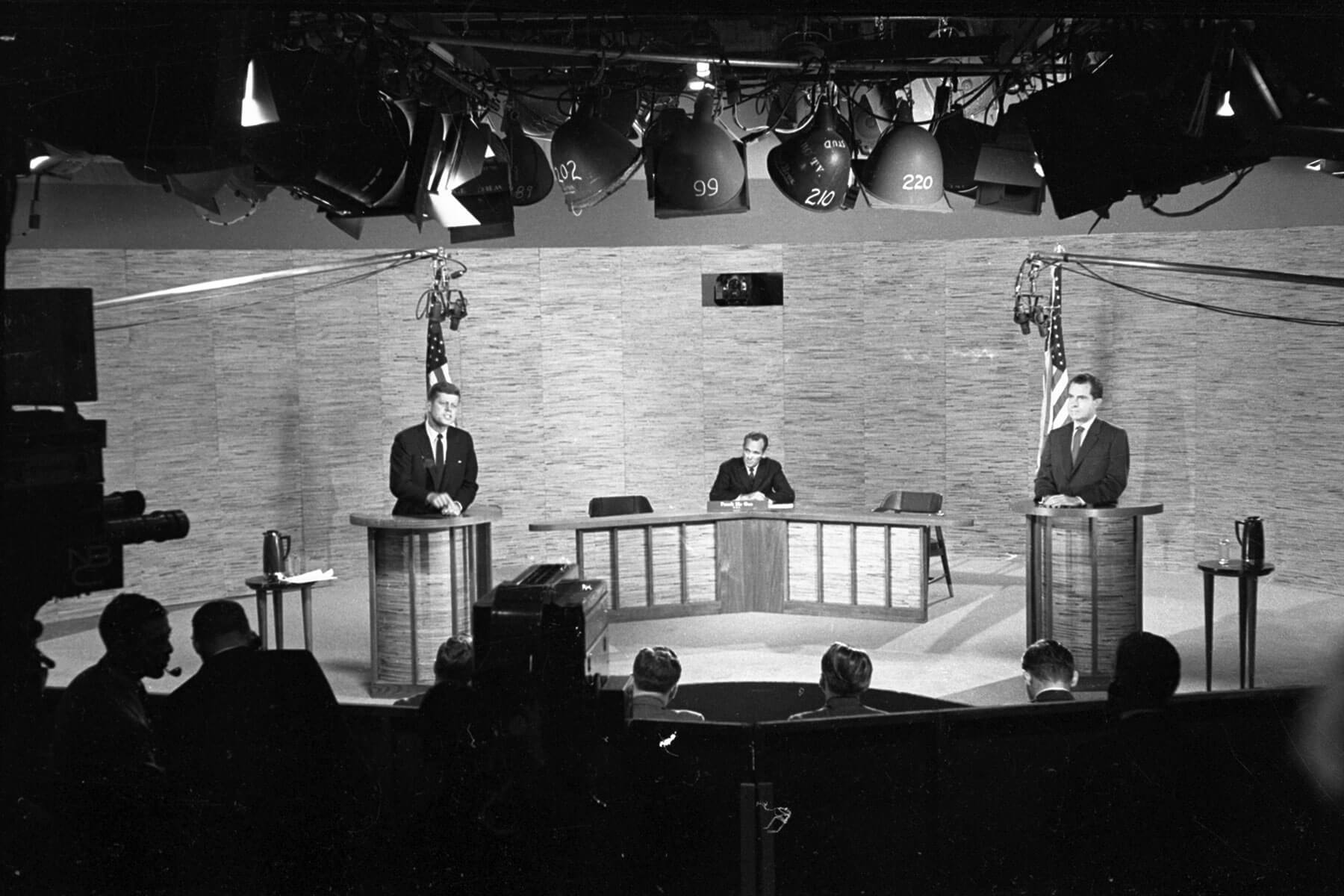

The First Laugh Track

Laugh tracks are an indelible part of sitcom television, and it all began in 1950 with a little-known program called The Hank McCune Show. The sitcom debuted on local stations in 1949 and centered around a fictional television variety show host. By the time the series made its network debut on September 9, 1950, it was accompanied by roaring laughter from a laugh track despite the lack of any live studio audience. One review from Variety magazine said, “Although the show is lensed on film without a studio audience, there are chuckles and yucks dubbed in… the practice may have unlimited possibilities.”

The laugh track was invented by mechanical engineer Charles Douglass, who was formerly a radar technician in the Navy. After leaving the military, Douglass created a device that came to be known as the “Laff Box.” A rudimentary version of Douglass’ invention debuted on The Hank McCune Show, though it took him three years to perfect his invention. Each 3-foot-tall Laff Box was handmade by Douglass and could hold 32 reels of 10 laughs apiece. By the 1960s, Douglass was supplying his much-coveted Laff Box to such iconic television programs as The Munsters and Gilligan’s Island.