People used to be buried with bells attached to their coffins in case they woke up.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, fear of being buried alive was widespread. Newspapers and pamphlets — not to mention gothic novels and “penny dreadfuls” — reported cases of mistaken death, and even famous figures took precautions to avoid being buried prematurely. Composer Frédéric Chopin reportedly asked that his body be cut open to ensure he was truly dead, while George Washington had his body watched for two full days before burial.

The concern was not entirely unfounded. Death is a gradual process, and faint pulse, shallow breathing, or illnesses that mimic death could easily fool the untrained observer. Early methods to confirm life included placing a feather by the mouth or using a mirror to detect breath. Later, more inventive techniques emerged, such as brushing invisible silver nitrate messages onto glass above coffins; decomposition gases would reveal the words “I am dead.”

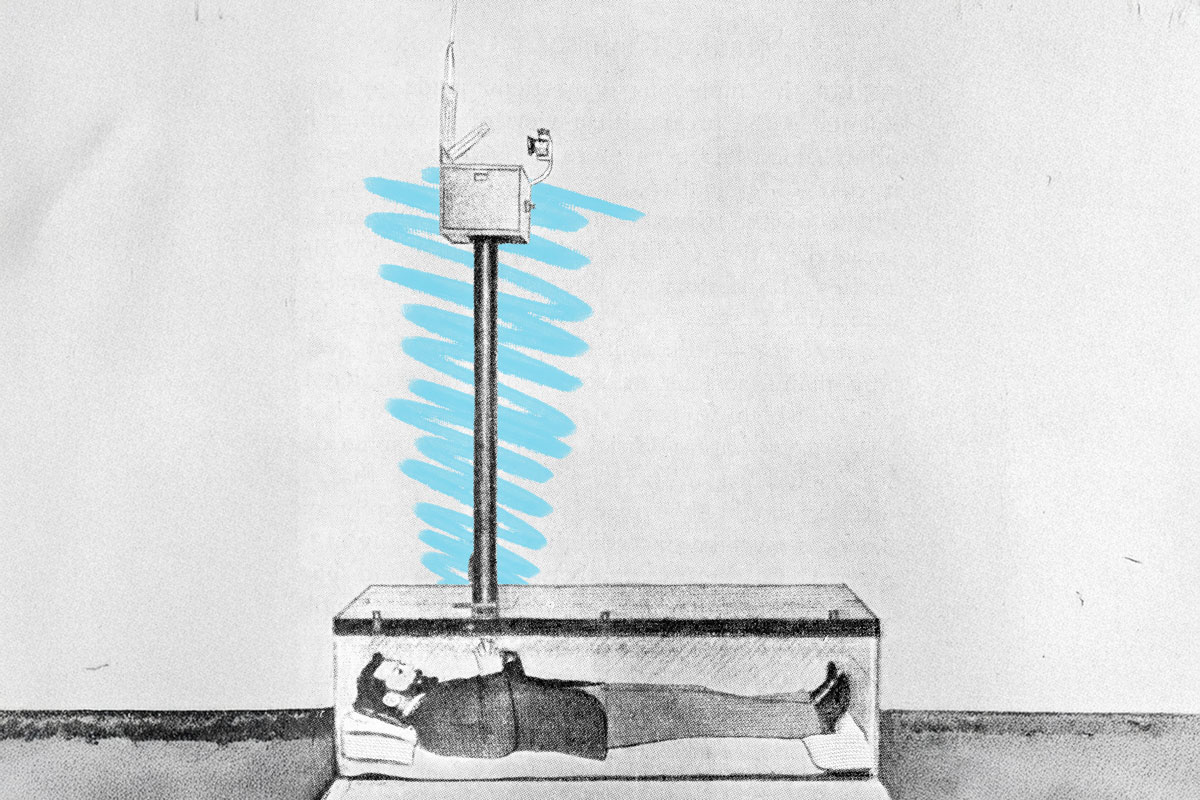

Fear of premature burial also inspired a wave of “safety” innovations. The most famous was Russian Count Michel de Karnice-Karnicki’s 1897 safety coffin, known as Le Karnice. A spring-loaded ball rested over the chest, and any movement released air and light into the coffin, which rang a bell and raised a flag aboveground. A tube allowed a conscious occupant to call for help.

Thousands of French citizens requested Le Karnice in their wills, and it was demonstrated in New York, though false alarms caused by natural postmortem body movements kept it from widespread use. Other safety coffins were also patented and demonstrated, including one in New Jersey that included a receptacle for refreshments.

While there’s no evidence that safety coffins actually ever saved anyone, they reveal a fascinating mix of ingenuity and anxiety. They are a reminder that for centuries, people sought practical ways to assert control over one of life’s most unsettling uncertainties: the line between life and death.