Who Was John Hancock?

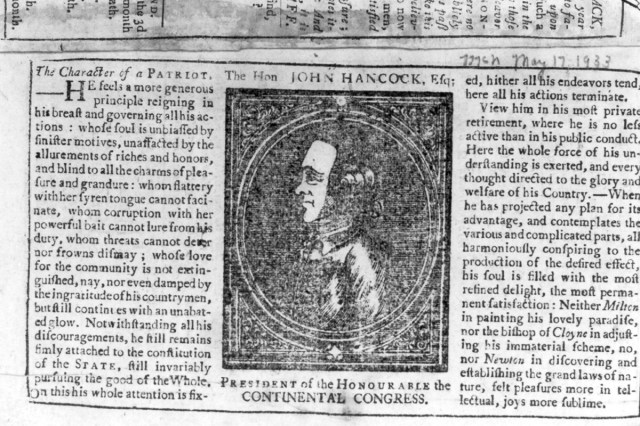

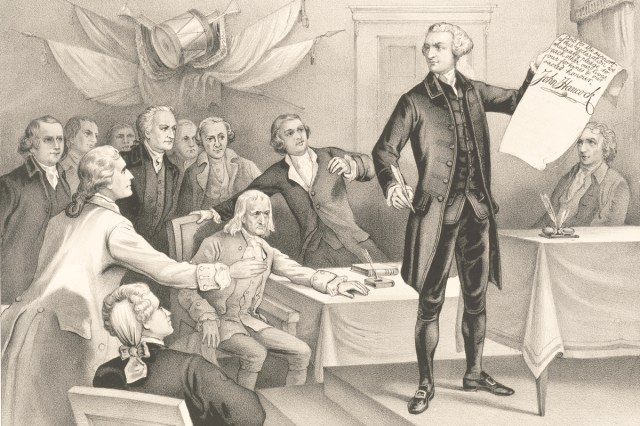

The apparent one-hit wonder of the U.S. Founding Fathers, John Hancock is largely known today solely for inscribing the first and largest signature at the bottom the Declaration of Independence — an act that resulted in his name becoming a synonym for the legally identifying scribbles we apply to checks and other important forms today.

It may seem curious that Hancock’s name stands front and center among the signatures on this most cherished document of American history, ahead of far more famous founders such as Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, or Benjamin Franklin. Yet Hancock was very much a leading man of his time. His reputation rendered him worthy of the handwritten flourish that placed him first among the luminaries who called for independence on July 4, 1776, even if his memory has all but vanished beyond the contours of that famous signature.

Rise to Wealth and Prominence

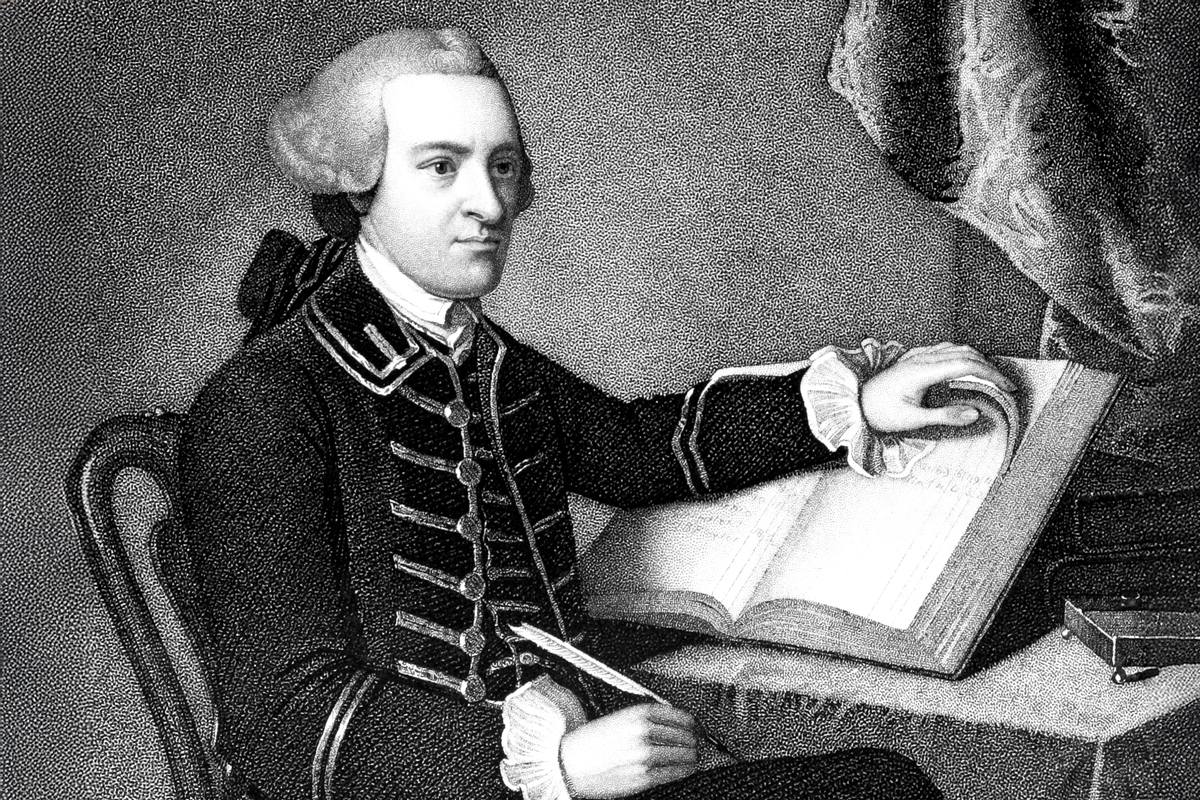

As described in Brooke Barbier’s biography King Hancock, John Hancock was born on January 23, 1737, in Braintree, Massachusetts, the son and grandson of Harvard College-groomed ministers (also both named John). Hancock likely would have headed down a similar career path, but his life took a sharp turn after his father died in 1744, and he was sent to live with his wealthy uncle, Thomas, in the large port city of Boston.

A largely mediocre student — although he proved adept at penmanship — Hancock went to work for his uncle’s import-export business after graduating from Harvard in 1754. He became a partner after a stint overseas in London in the early 1760s, and then inherited the firm following Thomas’ death in 1764. As befitting a man who then ranked among the wealthiest in Boston, Hancock was named a city selectman in 1765, before earning election to the Massachusetts House of Representatives the following year.

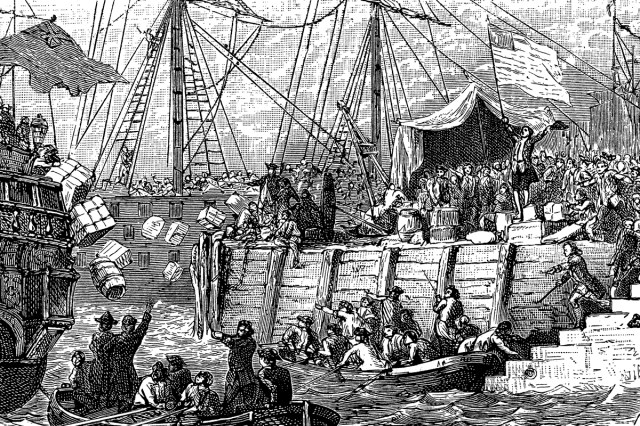

His rising social and political clout came at a time of increasing tensions toward the British Parliament, with many Bostonians frustrated by the taxes imposed by the Sugar Act of 1764 and the Stamp Act of 1765. A merchant with strong business ties to London, Hancock did not share the rebellious viewpoints harbored by local firebrands such as Samuel Adams and James Otis. Nevertheless, he joined a network of merchants who agreed to stop importing British goods as long as the Stamp Act remained in effect, an endeavor that proved successful with the act’s repeal in 1766.

Hancock’s shift toward resistance leader continued following a new round of import duties with the passage of the Townshend Acts in 1767. Drawing suspicions of smuggling from the local customs board, Hancock was celebrated for ejecting a pair of prying customs officials from one of the ships. Another of his vessels was seized two months later, and he was arrested in the fall of 1768 for smuggling, before getting the charges dropped the following spring with the help of lawyer and childhood friend John Adams.

Meanwhile, Hancock was among the group of assemblymen who helped draft the widely distributed “Circular Letter” that argued against the Townshend Acts, and he was also among the majority that voted to reject British demands to retract the letter. Two years later, following the violence of the Boston Massacre on March 5, 1770, Hancock chaired a committee that demanded the removal of British soldiers from Boston, and he agreed to oversee their safe and orderly withdrawal via the harbor.